Arte Fiera at 50: a vast and somewhat dizzying art display

Arte Fiera returned in 2024, from 2nd February to 4th February, with its 50th anniversary. The milestone is so significant that this year’s concept revolved precisely around it, wanting also to highlight how the ‘70s in Bologna were “an extraordinary decade in which the city was at the vanguard (not only in Italy) of visual arts, design, architecture, and in terms of conceiving new forms of relations among art, politics, and society.”

On the press day, the morning kicks off with a press conference inside the Esprit Nouveau Hall, held by the fair’s Artistic Director, Simone Menegoi, and other representatives. Words are spent to celebrate the fair’s anniversary, to thank all the partners sponsoring the event, as well as to remind the journalists to take a look at Luisa Lambri’s photographs inside the Hall.

Her pictures are conceived for Opus Novum #6, a commission of a new work by a chosen artist that the fair assigns each year. Lambri’s photographs, which typically have a tendency towards abstraction and minimalism, reflecting on space and light, take a look at two specific buildings from Bologna’s cityscape. Quietly but potently dealing with architectural shapes, windows and light, these pictures offer a small taste of what’s to come inside the two main halls.

Before entering the actual fair, however, Menegoi also reminds the small crowd of journalists to stop with him in front of the entrance, where he then inaugurates recently departed Alberto Garutti’s final work, titled Every step I have taken in my life has led me here, now (2024), consisting of a stone slab on the pavement with the titular sentence etched on it. Menegoi states that there is no plaque or inscription with the artist’s name on it, as this was Garutti’s initial intention. Standing in front of the stone, the viewer is brought to reflect on their own journeys, both literal and metaphorical: Garutti’s last piece seems to meditate on the condensation of time spent moving and living.

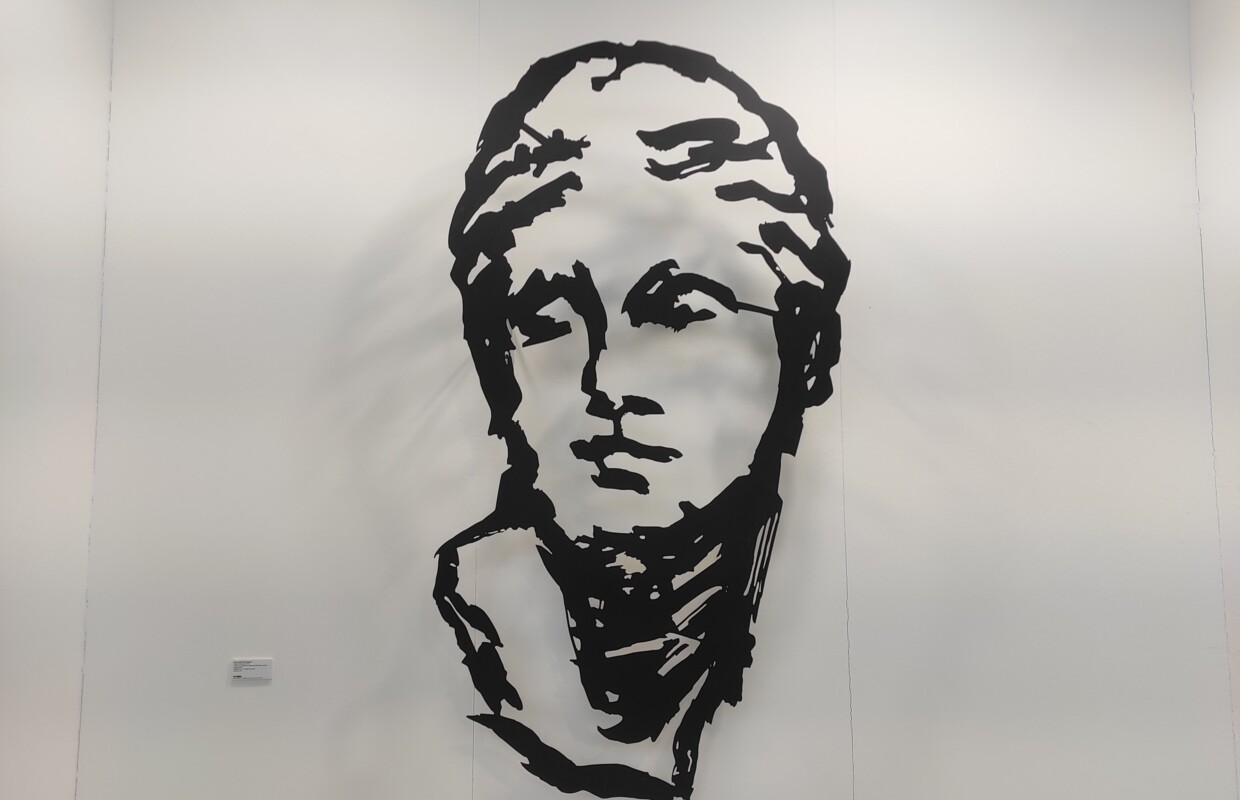

After this, it is time to venture inside the fair’s two main Halls, 25 and 26, which house an incredible total of 171 galleries/exhibitors. On entering the Main Section (which displays post-war and contemporary art) in Hall 25, the spectator is greeted immediately by a couple of interesting paintings by Polys Peslikas, with colors verging from pink to purple, courtesy of Vistamare Gallery. One painting in particular, titled Through the relentless swing of harsh summer, bodies persist in the wild display of love, depicting a person sitting down while reaching their ankles with their hands, communicates a sense of melancholy and dejection in a striking way. Lia Rumma’s booth also shines with works by William Kentridge, such as the imposing stainless steel sculpture Head (Venus) (2016), as well as the mysterious bronze “painting” Marching (2021), with its rectangular shape and background colour akin to copper.

Walking forward, you approach this year’s perhaps most anticipated artwork by Italian artist and provocateur Maurizio Cattelan. Because, his project, curated by Mutina for Art (Mutina is a brand that works in ceramics), consists of a wide booth decorated with orange terracotta courtesy of Michael Anastassiades, at the center of which stands a black canvas with a Z slashed on it (reminiscent of Lucio Fontana’s famous Concetto Spaziale series) and a small black sculpture of a cat, standing in one corner with its back to the viewers.

What is the relation between the canvas and the cat? Why are they both black? Why are they placed inside this terracotta space and what is this material’s significance? One might wonder if the cat looking away might not represent the public itself, watching the wall but not the canvas, or if Cattelan is asking us to choose which of the two subjects, canvas and cat, are more deserving of our attention. Speculations aside, Because remains an enticing if enigmatic work from the Italian artist.

Moving on, we find inside Michela Rizzo Gallery (Venice), according to her own words, “three artists who all have a connection to the art of cinema”. One of them in particular, Francesco Jodice (who is also presenting at Arte Fiera his newly published photography book West), deals with the iconography of the American West, as is conveyed through films and pop culture.

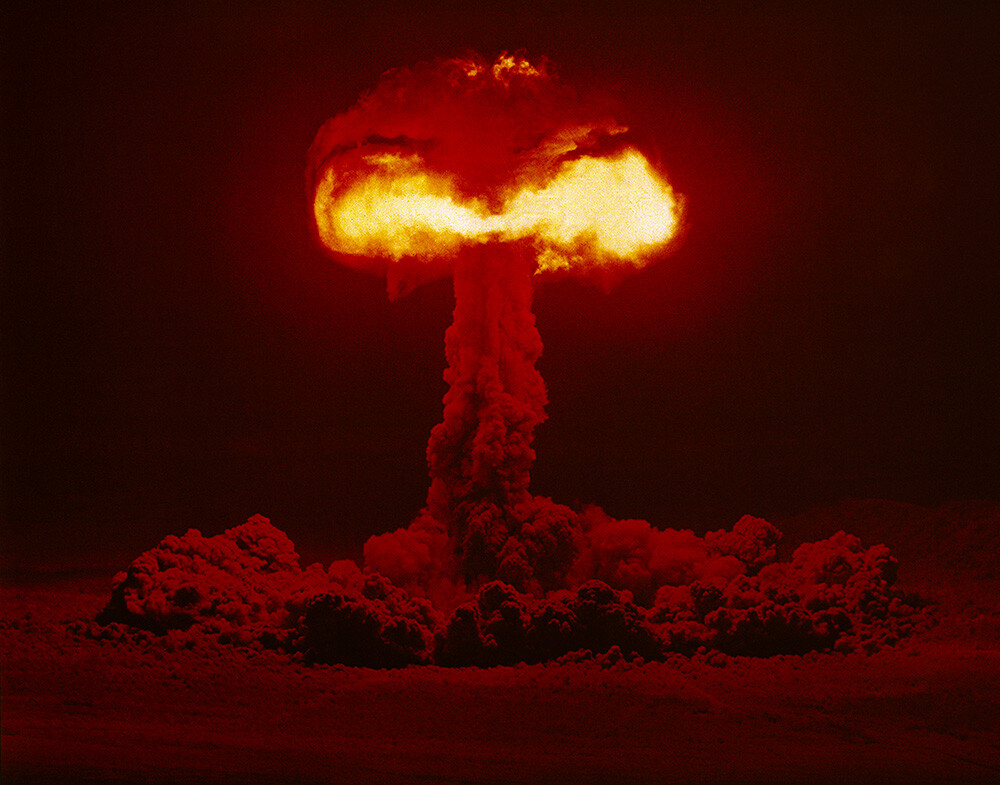

As Rizzo explains, Jodice sees in Lehman Brothers’ 2008 bankruptcy the beginning of the decay of Western civilization, and his photographs live in its aftermath. Especially striking are the photographs West, Tonopah, Nevada, #007 (2014), capturing the mushroom-like smoke cloud after an atomic bomb has gone off, as well as the diptych The Surfers (2023), which frames a crowd of surfers still in place staring at the far off horizon, whose white haze effaces any trace of a landscape.

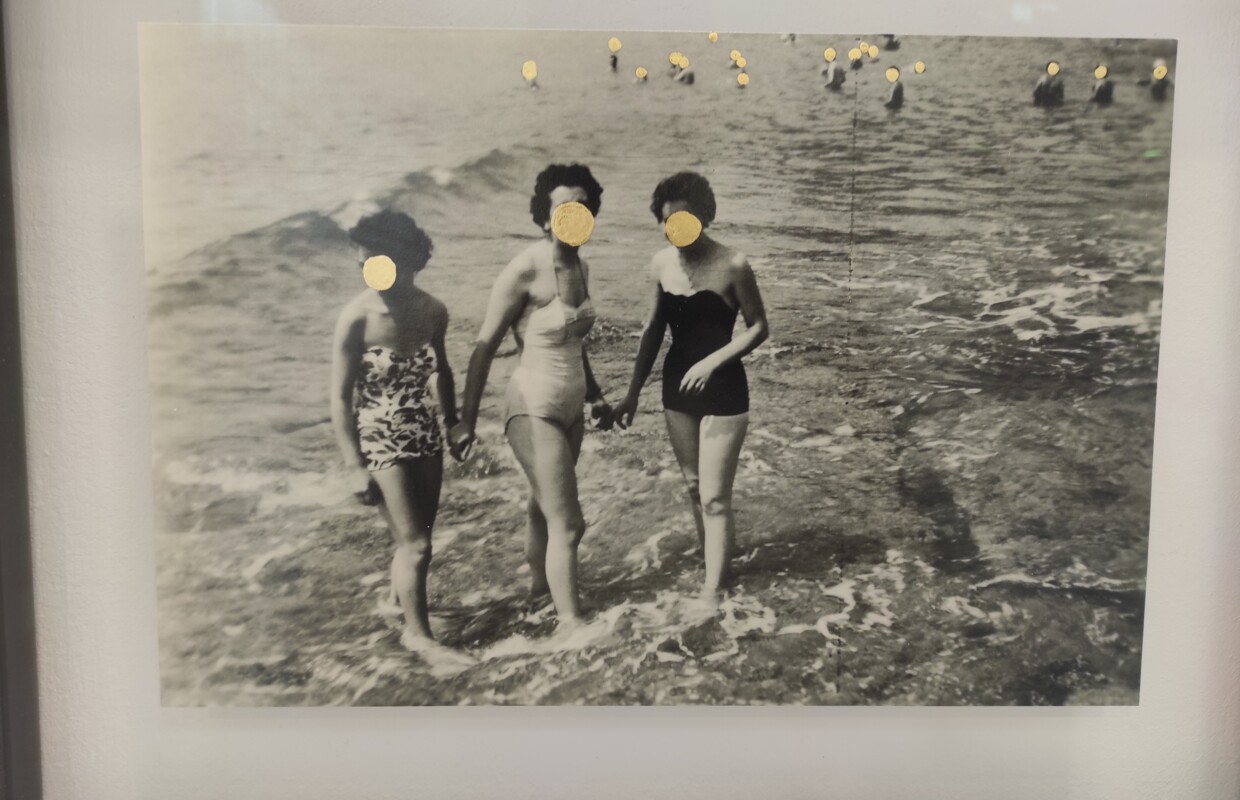

The Photography and Moving Images section of the fair proves to be quite appealing, as well. For example, you can marvel at Carolle Bénitah’s peculiar photos inside Alessia Paladini Gallery (Milan). It is Paladini herself who explains to me that her gallery’s intent for this year was to showcase three female artists, who all reflect on women’s role in society and convey a melancholic feeling connected to this. I suggest to her that Bénitah’s pictures seem to reflect profoundly on memory and time, and Paladini agrees, while also stating that Bénitah, as a self-proclaimed “artiste plasticien” does not simply take photos, but modifies them, too.

This is quite evident in her series Jamais ne t’oublierais (2023), where she applies pieces of gold leaf, as Paladini reports, in order to “delete some faces and to create a sort of universal family photo book full of happy memories”. Bénitah’s other series on display, Le jour le plus beau (2021), reworks the same photo many times so that by the end the actual picture is completely degraded, which functions as “a reflection on the photographic medium itself”, as Paladini makes clear to me.

Alongside these more established galleries, however, there is also space for some emerging artists and galleries.The Academy of Fine Arts of Bologna presents works from particularly deserving students, selected by curator and professor Marinella Paderni, as Ginevra (a student there) points out. Ginevra also explains that the exhibition, called The uncanny effect, takes its cue from the infamous “uncanny valley” phenomenon, whereby something is perceived as near-human even though it is not, and therefore induces a feeling of anxiety and terror.

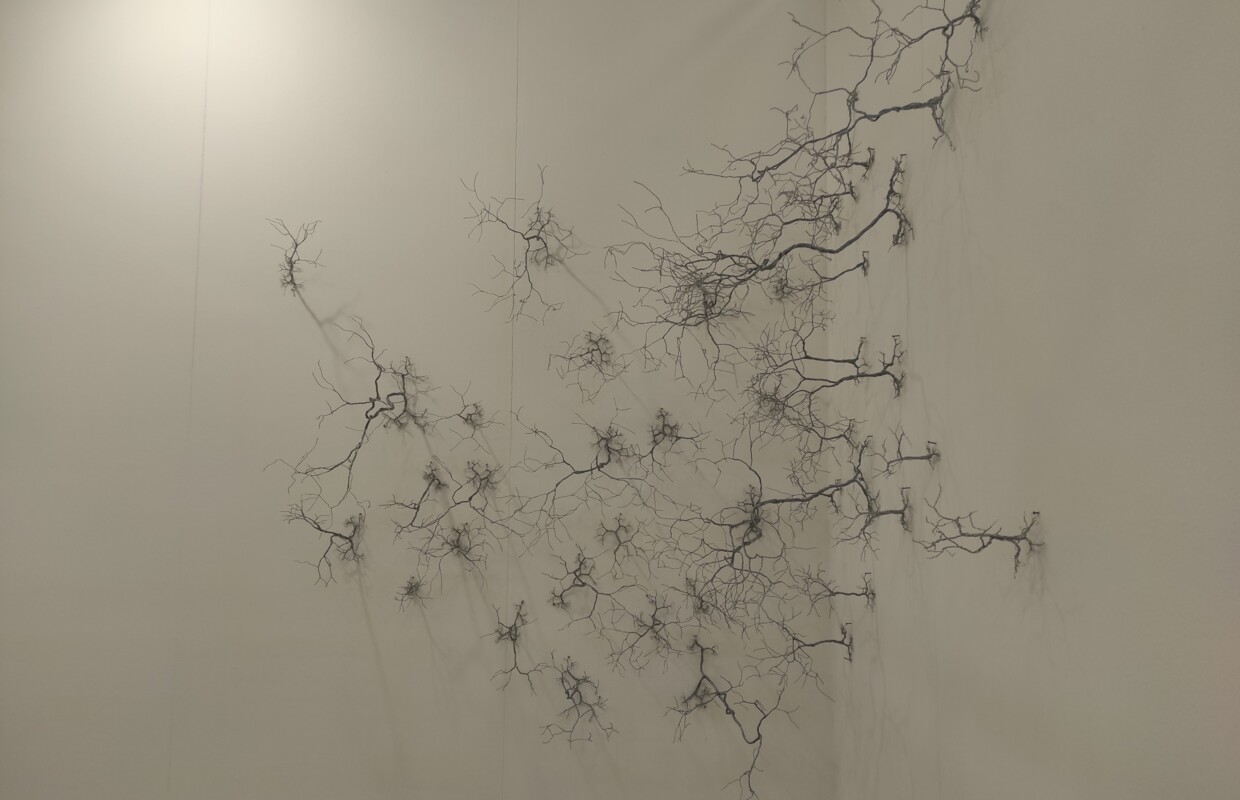

Particularly interesting in this sense is Yuxin Shi’s metal wire sculpture, Sotto il sogno di ferro (2023), which, as Ginevra states, asks the viewer what happens when there is no more nature and only industrial material is available to us. The sculpture takes the form of tree branches sprouting from the walls, but one could also view them as neurons from our brains, giving this art piece an even more disturbing aura. Another curious artwork from this group are Luca Finotello’s photographs, Obscura deconstruction of a landscape #4. Ginevra remarks that the artist turned his bedroom into a photographic darkroom, covering the walls with photosensitive paper where the small shafts of light coming from outside reacted on the paper creating some mysterious images.

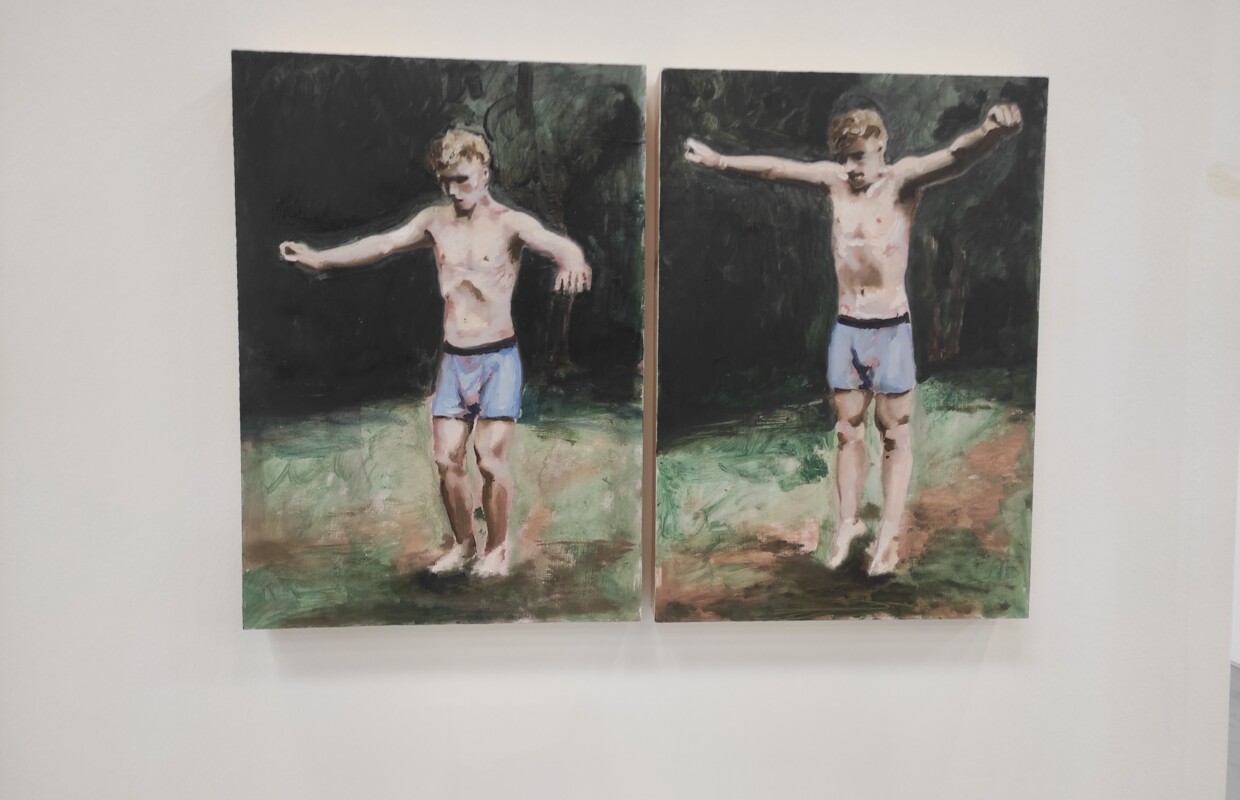

Fondazione Bevilacqua La Masa’s stand also displays 15 young artists (18 to 30 years old) who have won its atelier’s call for artworks, as Asia Donadel and Marta Gradenigo report to me. They observe that there is no overarching theme to La Masa’s display, but that each artist presents their most significant artwork. Worth mentioning here is Jacopo Zambello’s painted diptych of a young man about to jump into the water, which conveys a sense of anticipation mixed with dread.

As far as renowned artists go, the fair-goer can encounter plenty of paintings by Carla Accardi, for example Due rossi con blu (1962) or Untitled (1958), in Mucciaccia Gallery’s possession, or Emilio Isgrò’s Fratelli d’Italia triptych (2009), on sale for a whopping 200k at L’incontro Gallery; and even two works from Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale series (1964) alongside a Natura Morta (1961) by Giorgio Morandi, all on the walls of Tornabuoni Arte gallery.

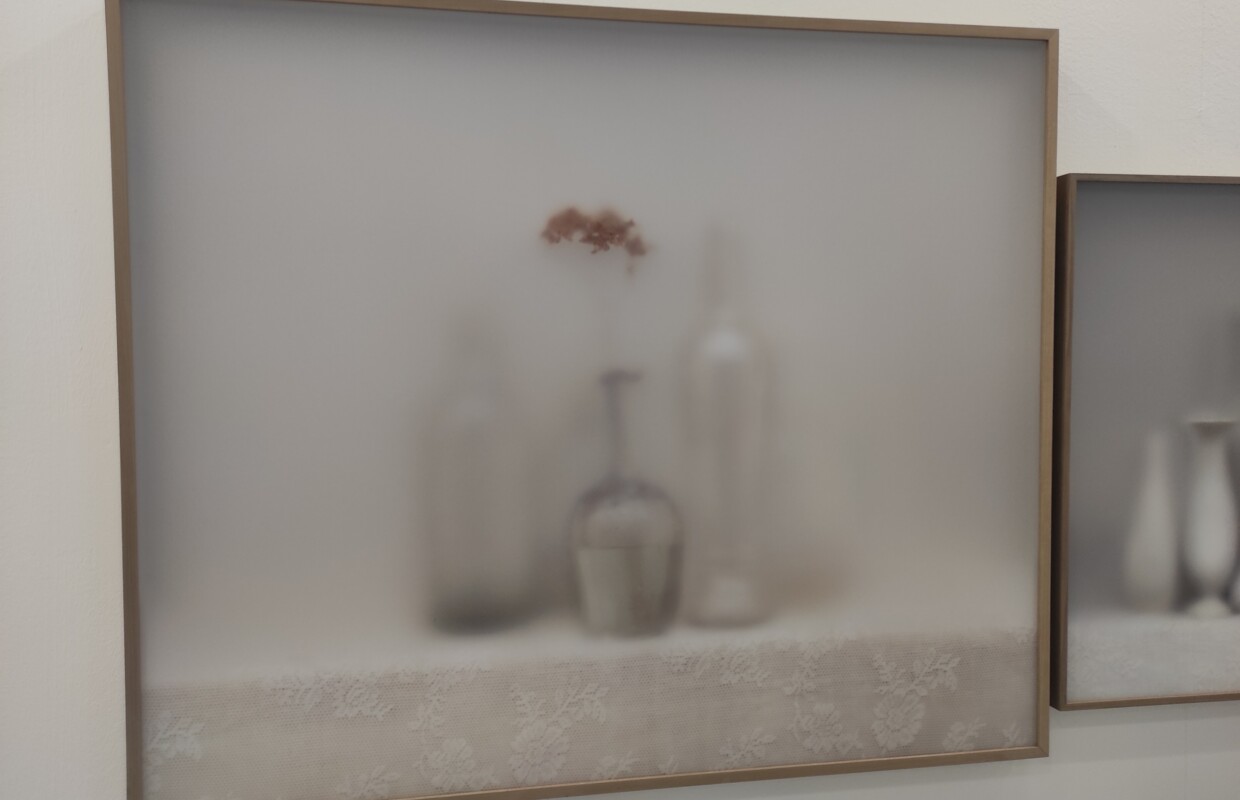

En passant, Umberto Di Marino’s gallery stands out with eye-catching works by Alberto Di Fabio (Spazio, Materia, Tempo, 2020), Peter Böhnisch (Untitled, 2022), and Marco Giordano (Ebbbe and Tidedit, 2023), while Spazio Nuovo presents some captivating photographs of a tranquil seascape in three slightly different settings by Giuseppe Lo Schiavo (A Glass of Ocean, 2023). In addition, it is worth noting the fascinating mixture of photography and oil painting at the hands of Casper Faassen, for MC2 Gallery, depicting objects and subjects shrouded in a thin veil, as if seen through mist.

In addition to all this, there was also time for a performance by Daniela Ortiz held inside Hall 25. Titled Tiro al Blanco, it consisted of a wooden stall reminiscent of a typical fair stall where the public could play shooting targets, except in this case the targets were drawings on metal plates of military weapons, airplanes, bombs, companies, and so on. The performance begins with a young man explaining the game Ortiz thought of: taking turns, people from the crowd who were given a pink ticket earlier could step in front of the stall, take a shotgun and shoot at the targets, in a metaphorical effort to take down the Western military complex.

At the same time, the young man recited aloud the specifics of the different companies or weapons that were being hit, interspersed with facts and statistics about wars (past and ongoing). The shooters who managed to hit a target would win some small prizes, like a marionette of a “Vietcong” that acted like a slingshot. With a very ironic and sharp concept, this performance invited the public to become involved in dismantling the military complex that continues to engage in wars across the world, transforming a game from a funfair into something much more serious.

From the interviews I conducted during the fair, when asked if the exhibitions were planned with Arte Fiera’s 50th anniversary in mind, the gallerists I talked to all responded in the negative. Why then promote the importance of the anniversary as the fair’s concept if the exhibitors do not follow it? It seems clear that Arte Fiera works mainly as a platform to promote and sell artworks, rather than a curated exhibition, but at any rate the lack of a common theme becomes immediately evident and, because of the large amount of artworks, it risks becoming a potpourri of numerous pieces without a proper throughline.

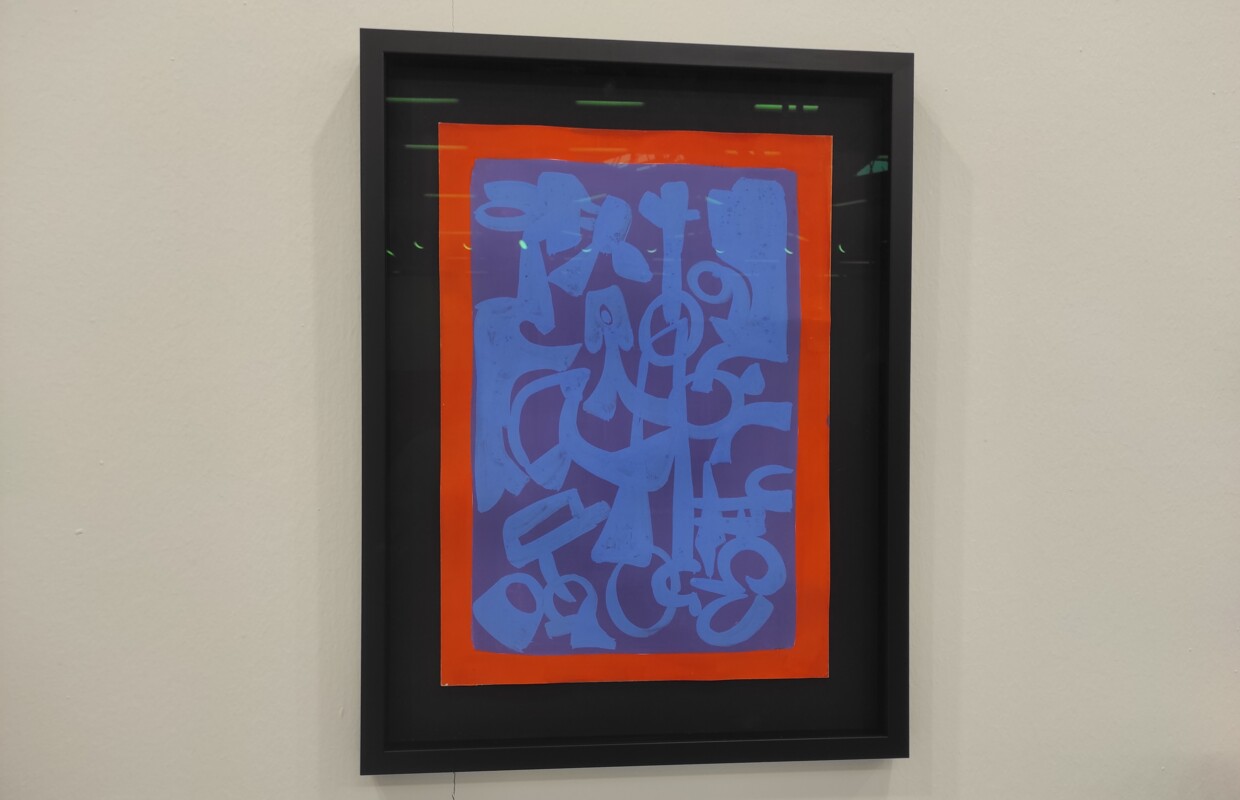

In this sense, if visitors would like to visit some smaller and more structured exhibitions, Arte Fiera also promotes various events throughout Bologna under the “Art City” umbrella. I visited two that were connected to the 60th anniversary of Giorgio Morandi’s death: one was Tacita Dean’s 16mm short film, STILL LIFE. The Studio of Giorgio Morandi (2009), which displays the artist’s meticulous sketches, and the other were American photographer Joel Meyerowitz’s stills of Morandi’s Objects (2015), portraying the everyday objects that became the subjects of Morandi’s paintings. Another small show was dedicated solely to Austrian artist Greta Schödl, whose works are characterized by the repetition of words written or painted over everyday objects, which produce enchanting visual patterns.

Overall, Arte Fiera is an art fair with international ambitions that wants to showcase an astounding number of artworks, from established artists and newcomers alike. And in its emphasis on curation, it aspires to blur the lines between fair and exhibition. But while the scope is big, perhaps it risks becoming too much for some.

Share the post: