Demilitarisation through art

Marta Czyż about Autostrada Biennale in Kosovo

Kosovo, one of the youngest states in the world, was created in 2008. It is a country in the midst of both a new state-building process and a process of reconstruction after the traumas of the Balkan wars. In a country whose citizens can travel visa-free to two countries, a cultural initiative has emerged that provides a space for artists and audiences hungry for contemporary art. The Hangar Autostrada is an initiative that has taken over hangars at a former NATO base in Prizren (the second largest city in Kosovo). Workshops, meetings and many creative activities take place there. They culminate in the Autostrada Biennale. For the last two editions (2021 and 2023), it has been curated by Övül Ö. Durmuşoğlu and Joanna Warsza. The first edition by them had the title 'What if a journey...', in 2021, asking the question of what it means for something to be unfinished. This year's second biennial title 'All images will disappear one day' reflects on the archive as an intangible element of culture.

Many questions arise today about the production and care of cultural resources, but also about how to create Biennale events today given both the various global crises, if only the climate, at a time when many institutions are experiencing an inclusive turn. As one of the younger events of its kind, the Autostrada Biennale seems to be a model example of a sustainable art event.

An event in which ephemerality and commerciality are replaced by lasting change, and works become monuments that penetrate and create the identity of a young country.

The Biennial and the activities of Autostrada Hangar leave a lasting mark not only in the form of catalogues and other publications, but also in the changes that take place in minds and spaces.

The co-founders of the Autostrada Hangar initiative are Vatra Abrashi, Leutrim Fishekqiu and Barış Karamuço. They come from a variety of disciplines. Vatra is an educator and therapist, Leutrim works in sculpture and design, Baris studied photography but is also a filmmaker. They live in Prizren, a city that is very diverse, a cultural heritage of the region, but home to many young citizens who do not have a space in which to express themselves. They also do not have the opportunity to visit and exchange with other art institutions, for the reason that they are not here. Vatra, Leutrim and Barış created a platform to exchange experiences and promote the city, but ultimately they wanted to create a Biennale event. Kosovo is the only country where there is no visa liberalisation, so people do not have the opportunity to visit other biennales, even though Prizren is 180km from Venice and 100km from Istanbul. The creators saw Autostrada as connecting cities, connecting countries, not just being local and creating culture locally.

The slogan 'autostrada' (highway), symbolises a new road, a bridge to connect cultures and facilitate the reconstruction process.

Abrashi, Fishekqiu and Karamuço created a platform where local artists could create and be part of an artistic community, express themselves and, in this isolated country at the centre of Europe, connect with various international institutions. This is how the Biennale began. From scratch.

From the beginning of Hangar's work, its creators were guided by the idea of art for the people, not people for art.

Art began to enter buildings, public spaces, the castle, townhouses, narrow streets, private houses, the bus stations and various places that belong to everyone and thus became immediately part of the creative space. From the beginning of the Autostrada Biennale, the aim of its initiators was to reach out to different audiences. By design, the project was intended to be inclusive and not exclusive, as most events of this type are perceived.

In 2016, the creators of Autostrada Hangar organised an international conference to which they invited curators from all over the world, and the main idea was to discuss the impact of a new biennial in this part of Europe and specifically on the city of Prizren, but also on the whole region and how to organise a biennial in a city that has no galleries or art institutions. From the beginning, there was a lot of interest from the local community and regional partners. An advisory board was then formed. It was they who suggested curators for the first editions of the Biennale (four have been held so far).

It looks from a distance like a utopian vision: working without a budget, acting locally, working with schools, getting young people interested, creating creative jobs. However, it only took a few years to clearly congratulate Autostrada Hangar on its success on every line. It turns out that you don't have to be a San Francisco start-up and have the support of influential and wealthy people to realise a vision you believe in.

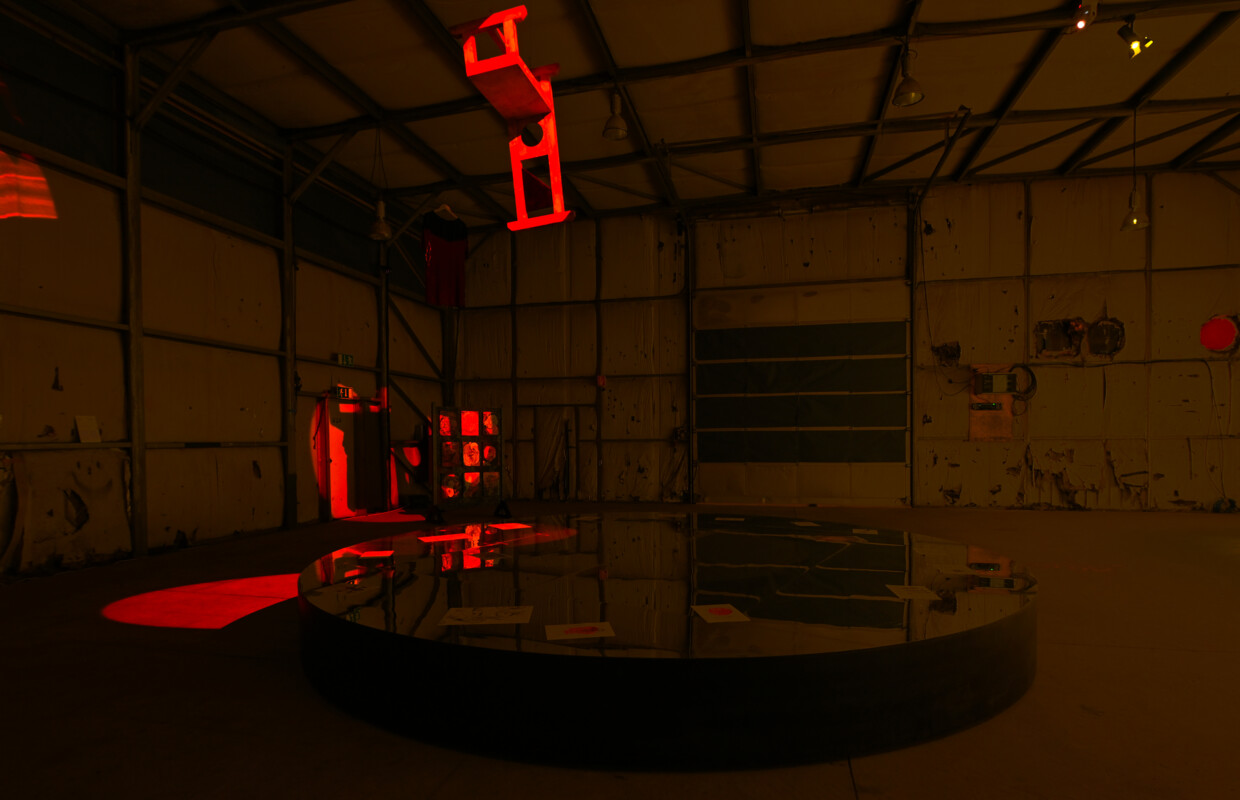

By entering the former NATO military base in Prizren, which for many years was a kind of extraterritorial space, we cross the border into creative space.

The hangars annexed by Autostrada are a space for meetings and workshops, but also a place to come and create. Every element that fills the place is for something, but it also has no single purpose. The furniture is mobile and can serve different functions, the space can be divided, there are assembly stations, woodworking stations. There is an activity taking place at every moment. The Biennale is the cherry on the top; it is a meeting that unites, but also leaves a lasting mark.

This mark also includes works that do not disappear after the Biennale closes. This gesture is also thoughtful and underlines the sustainable aspect of this project. The selected works correspond interestingly with the heritage of the emerging state.

In the centre of Prizren there is a work "In the depth of the night the sky sees the sun?" by Iranian artist Neda Saeedi, who lives in Berlin and makes stained glass using old techniques from Persia. Saeedi created the work inside the huge plinth of the Partisan Monument, symbolising the history of migration. There she created a stained glass window in the shape of a large lens of the eye, which resembles a kaleidoscope. This work became the visual theme of this year's Biennale titled 'All images will disapear one day' and is a work that asks questions about archives that are not material: about memory, which through art can become a permanent record of history.

There is an even more nostalgic story in the second work left in space after the Biennale closed. During the Yugoslav era, from the 1970s, in the centre of Mitrovica, there was a monument to 'Equality, Work and Education', depicting the outline of two men and a woman holding tools, a pigeon and a book, symbols of an idealistic, socialist society. The statue suddenly disappeared under mysterious circumstances in 2010. The artist, Alban Muja, created a miniature of the monument during the third edition of the Biennale, which aroused a lot of emotion. Information and speculation about its fate continued to emerge. In the latest, fourth edition, Muja restored the monument in full scale to its old place. In the end, the ideas promoted did not become obsolete and today they can talk about the resilient development of the young Kosovar society. "Moving monument - moving back" is also about restoring idealism and balance and an objective approach to history.

A final important element is that the Biennale does not close only to Prizren. The aforementioned project was created in Mitrovica. Also there, an exhibition took place in the independent space 7Arte. In Pristina, Agnes Denes' Field of Sunflowers and Hera Büyüktaşcıyan's “Who speaks from the dust, who looks from the clay” were on display at Brick Factory. Where the next Biennale will be held is yet to be seen, but this art-highway is already ready to welcome more high-profile art.

Share the post: