Is a queer Biennale really possible?

An overview of queer artworks and a talk with Agnes Questionmark and Frieda Toranzo Jaeger.

Biennale 2024 opens its doors to “Foreigners Everywhere”, inviting all artists who, metaphorically or not, are “foreigners”, strangers in a certain land, outsiders in society, indigenous, queer, marginalised. This article, rather than being a summary of all the Biennale’s contents, tries instead to concentrate on artworks which incorporate queer themes or are produced by artists who openly declare their queerness.

Discussing this year’s theme, Biennale’s artistic director Adriano Pedrosa has explained the reason behind its choice, claiming that “wherever you go and wherever you are you will always encounter foreigners— they/we are everywhere” and also “that no matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner.” The phrase comes from a series of neon sculptures created by artistic duo Claire Fontaine since 2004, bearing the expression “foreigners everywhere” translated in various languages. It is also interesting to note that “the phrase comes, in turn, from the name of a Turin collective who fought racism and xenophobia in Italy in the early 2000s.”

Pedrosa’s curatorial text also looks at the etymological roots of the word “foreigner” and finds that in various European languages it is connected to the word “stranger”. In this sense, Pedrosa also creates a connection to Freud’s Unheimlich, the uncanny - that which feels both familiar and strange simultaneously. Besides, “according to the American Heritage and the Oxford Dictionaries, the first meaning of the word ‘queer’ is precisely ‘strange’”.

The exhibition takes these insights as its starting point, showcasing those subjects who, like queer people, have been historically cast as “strange”, “foreign”, or “other”, “unfamiliar”.

This is certainly a clear curatorial decision, firmly rooted in the domain of much queer and decolonial theory. Therefore, I approach this year’s Biennale with curiosity about how this concept is put into practice and whether it genuinely works or feels a little bit “late to the game” in terms of representing otherness and queerness.

Exhibited inside the Central Pavilion at Giardini, we start with Louis Fratino’s large-scale paintings. These depict mostly gay men, sometimes in intimate gestures or even during sexual intercourse, with strikingly bright colours and a frankness with regards to intimacy in the lives of queer men.

An example is «I keep my treasure in my ass» (2019), a painting that portrays a naked young man apparently giving birth to another young man, a scene both absurd and erotically charged. Another exuberantly queer painting of his is «Metropolitan» (2019), a large canvas depicting a group of naked men dancing and kissing in a multi-coloured ballroom. Whereas a painting like «An Argument» (2021), presents a “slice-of-life” situation. The viewer looks at two young men, both asleep, separated by a window-frame that signals the titular situation. In this apparently serene environment, a fight has happened, unearthing a layer of unexpected melancholy.

While Fratino’s works can be very direct, an artist like Dean Sameshima, with his photographic series «being alone» (2022), furtively captures men in the dark environment of an adults-only cinema in Berlin, a place which functions as a cruising spot, that is, a place for casual sexual encounters among gay men. Looking at these photos, the viewer may not immediately make this connection. One can only see the white square which is the cinema screen and the silhouettes of anonymous men sitting in various positions in the venue.

But the photos are taken from a slightly different angle each time: the white screen changes position in each picture, as if to indicate the oscillating desire that animates the people in that cinema. Secrecy pervades these pictures: the light from the movie screen is the only thing that lets us see these men, as if they only existed by refraction: once the lights go out, they disappear into darkness.

Inside the Arsenale, we find an artist whose work deals with queerness by focusing on technology, cars, the future, and liberation. Frieda Toranzo Jaeger’s huge canvas «Rage is a Machine in Times of Senselessness» (2024) mixes traditional oil painting - which, from afar resembles spray-paint - with embroidery to depict large-scale car parts with windows onto natural scenery. Small embroidered scenes present, for example, an orgiastic circle of naked women or two skeletons at the bottom centre of the canvas, possibly a sort of “memento mori” directed at the viewer.

In our conversation, Frieda explains to me how this work, because of its scale, references Mexican muralists like Rodolfo Morales, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco. She also wanted to include embroidery as an artform that is strongly tied to female craftsmanship, and one which takes up a lot of time, too. Its presence forces viewers to look closer at the canvas, as its details appear tiny from afar, especially compared to the size of the entire canvas.

While working on it, the war in Palestine broke out, and Frieda, as an artist who deals with decolonisation in her own practice, felt morally obligated to mention it in her artwork. On the canvas’ backside she writes the question “What is the work of the witness?”. To this, she replies, “it is to be marked”, to feel the horror of other people’s suffering and bear it on your own body and work.

When I ask Frieda how she feels about participating at the Biennale, she confesses her conflicting emotions, feeling both happy to be showing her artwork on this big scale, while at the same time questioning why she has been selected, what kind of politics influences an exhibition like this.

Even though Frieda is familiar with this year’s concept through Claire Fontaine’s work and considers it an important lens for the whole exhibition, she does not necessarily want to be reduced to the label of “queer” or “Indigenous” or being talked about as a “woman of colour”, because people often do not fit neatly into a single category.

This led me to wonder if she thought that these categories might feel outdated nowadays. Frieda responds that while we still need these terms and categories to discuss certain identities, she is more interested in seeing them as dialectical, as constant change happening in everyone’s lives.

“Being queer is always a state of becoming, and it’s also a very uncomfortable space,

When I ask her what she thinks of American queer theorist Judith Butler’s idea that through “inclusion” there is always a risk of re-colonizing and erasing the differences that were key to certain marginal identities («Gender Trouble», p.18), Frieda agrees that participating at the Biennale means becoming complicit with the same structures that have excluded non-conforming artistic voices in the past.

However, she is also convinced that her work offers a resistance to these same colonising, capitalist structures within the artworld. Besides, if there is no alternative to these frameworks, “you have to build it yourself”, going against the system internally. Finally, she remarks that, as a queer person, “I’m not about succeeding”, but she still tries.

Thinking about young artists who are just starting out, I ask Frieda how her university choices have helped her and what advice she would give to recent graduates. In reply, she stresses that the first thing that younger artists must change are the “systems of validation”, striving not to seek the approval of “renowned” curators or galleries. “We need to stop wanting to be rich”, she states, because those who might fund artists often may not even understand or appreciate their work. She acknowledges that there certainly are museums and galleries trying to change this dynamic, but it is still an ongoing process.

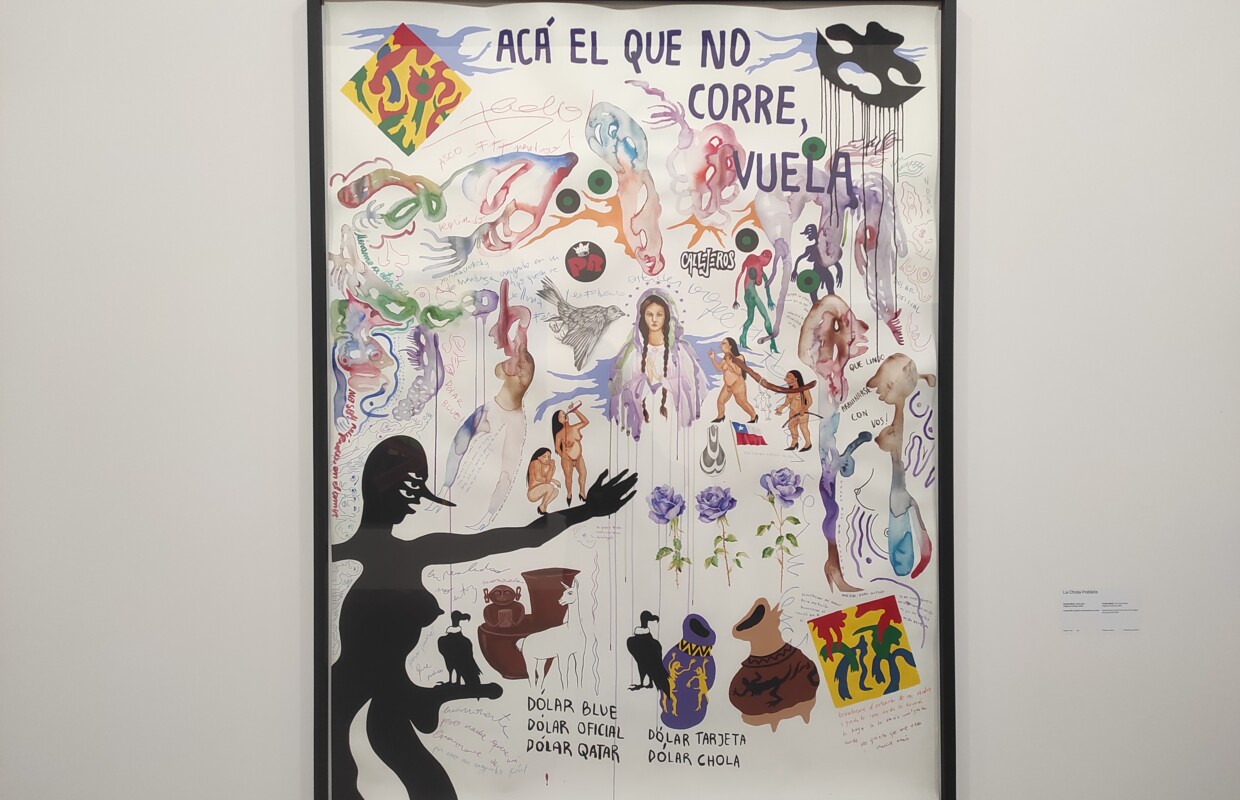

Moving on inside the Arsenale, visitors are captured by La Chola Poblete’s paintings: her works combine acrylic paint with watercolour and ink in order to craft canvases that straddle the line between street art and traditional painting. There are no identifiable scenes in these works. Instead, they are composed of painted figures, slogans, abstract motifs and a variety of colours on a white background.

A good example is «Purple Maria» (from the series «Virgines Cholas», 2023) which features precisely the Virgin Mary painted at the centre and a series of other naked women around her, an unidentified black figure with an erect penis at the bottom left of the space, and other painted motifs alongside some phrases. At the top stands a phrase: “Acá… el que no corre vuela” (“Here what doesn’t run, flies”), which, in my view, may allude to the capacity of bodies, especially queer and trans ones, to adapt and morph over time.

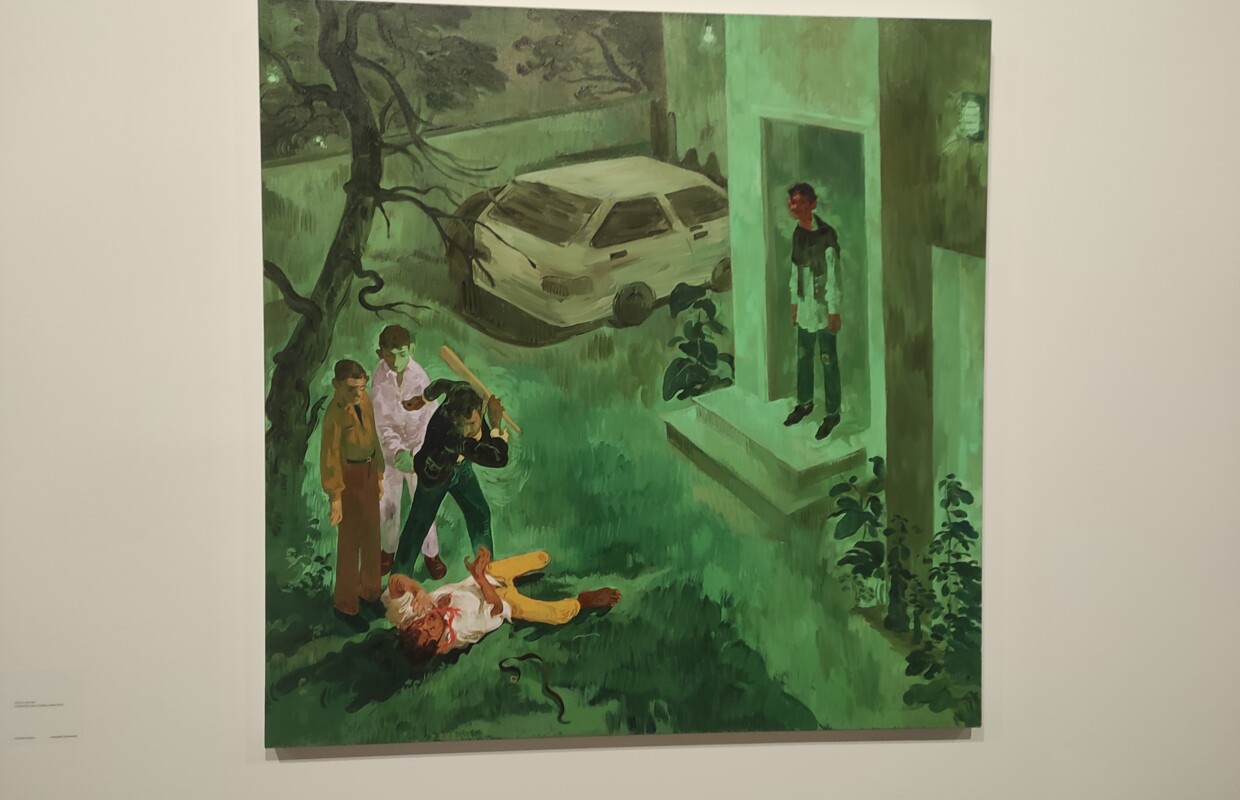

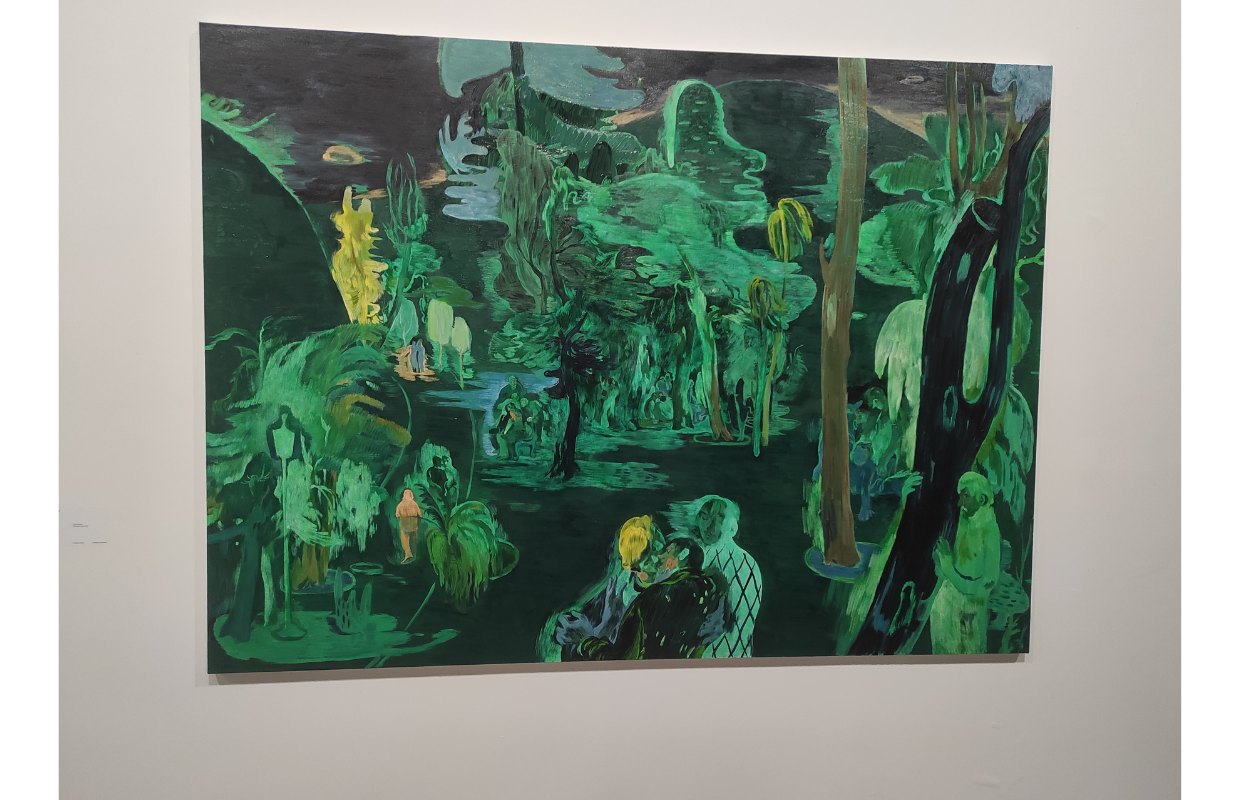

Next up, Salman Toor is an artist whose works seem to echo Louis Fratino’s output. His paintings also depict the lives of queer men, but their everydayness appears even more clearly. In some works the viewer could also trace some narrative tension.

Green seems to be a recurring colour in Toor’s artworks, as can be noticed in both «The Beating» (2019) and «Night Grove» (2024). In the former, the title is quite indicative. A man is on the ground in front of a house, being beaten up by a group of three men, while another stands not far, hands in his pockets, right on a doorstep. What I gathered is that the young man being beaten up may be the lover of the one standing impotently on the doorstep. All is immersed in green, except for the trio hitting the poor man on the ground. An atmosphere of sadness and immobility pervades the whole picture.

The latter painting depicts various men who are cruising in the woods: a couple in the foreground is sharing a kiss, while a naked man observes them hidden behind a tree on the right. This painting, too, is largely painted in green, while the background is mostly dark, hinting probably at the furtiveness of cruising. Some viewers may be reminded of a French film titled Stranger by the lake (Alain Guiraudie, 2013), that takes place at a lake that is also a popular cruising spot for gay men.

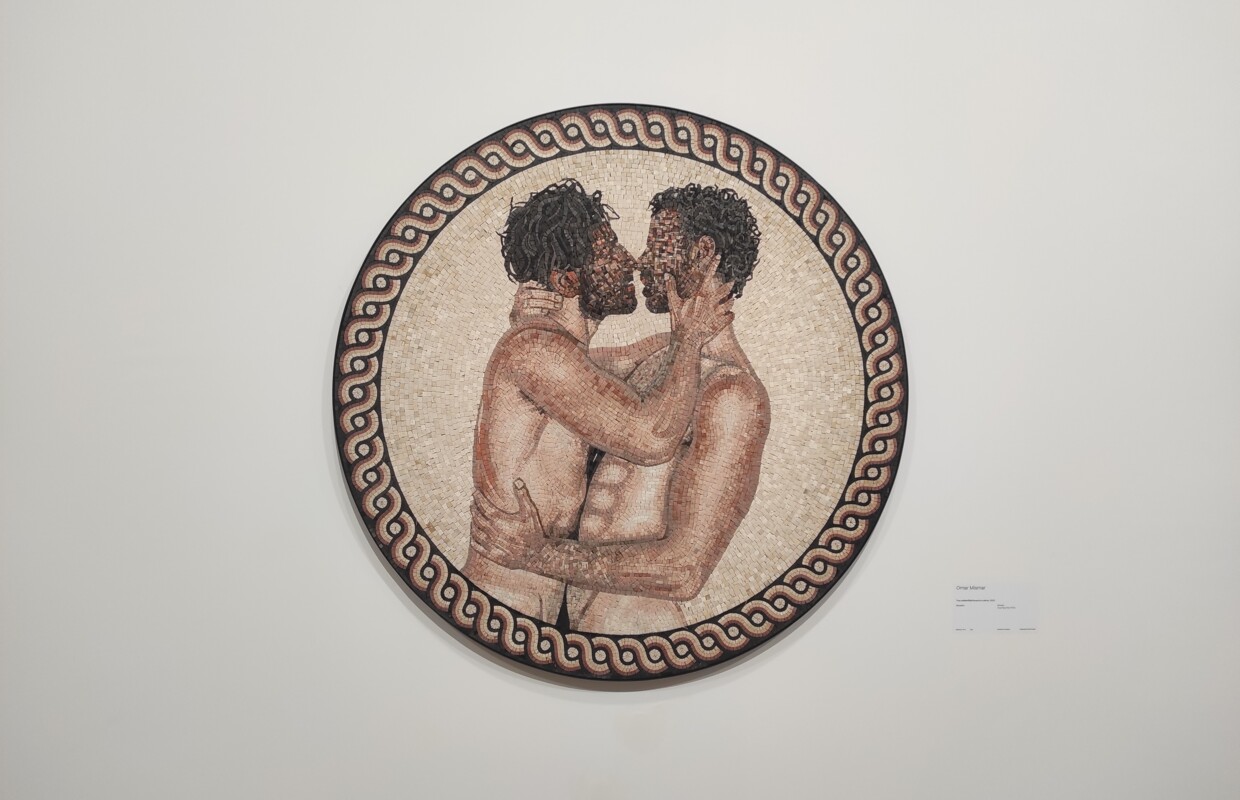

The artists mentioned so far are just a few among many others who offer interesting contributions to the general exhibition. Omar Mismar, for example, presents «Two unidentified lovers in a mirror» (2023), a mosaic which shows two bare-chested men embracing and kissing on a pale pink backdrop, with a circular motif framing the whole picture. The echo of Ancient Greek artworks is evident and the effect is unexpectedly striking.

Xiyadie takes the route of incorporating queer imagery into more traditional iconography or materials. His artwork «Don’t worry, Mom is Spinning Thread in the Next Room» (2019) utilises papercut with water-based dye and Chinese pigments in order to represent a scene of fellatio between two figures who may be men. While the subject matter is explicit, it is simultaneously reconfigured inside a type of painting that harks back to the ancient past.

Ana Segovia, on the other hand, reconfigures the stereotypical association between cowboys and machismo by portraying these men dressed in vibrant, sometimes neon colours, with the intention of bringing to light the latent homoeroticism of the western as a film genre. Her video installation «Pos’ se acabó ese cantar» (2021) shows two cowboys who seem to be quarrelling suddenly tucking in each other’s shirts, a gesture which displaces the violence and manliness usually associated with cowboys in the popular imagination.

If visitors venture towards the Arsenale’s gardens, they can find the four artists selected as part of Biennale College’s initiative. Agnes Questionmark, one of the selected four, shared her experience in our interview.

It started with applying early in 2023 and then - to her own surprise - being selected. She researched her project from September to November 2023 and spent the following months producing and installing her work, «Cyber-Teratology Operation» (2024). Agnes describes Biennale College as an intense workshop involving 12 artists who spend about 10 to 12 days together on San Servolo island in Venice - a small, isolated island off the mainland.

In a humorous way, Agnes compares Biennale College to “a bootcamp for a TV program”, as artists were under quite some pressure, due to constant reviews of their works by curators, but still maintained a relaxed attitude throughout. She also admits to forging strong bonds with other queer and trans artists, which gave her a feeling of recognition and protection from hostilities and negative remarks she faced while in Venice.

Agnes tells me that she did not think much about this year’s concept because she felt that her work already investigated those ideas. Feeling like a “foreigner” in your own body and reflecting on queerness and gender fluidity are themes that are filtered through her interest in surveillance systems and the medical apparatus. When she heard Biennale’s artistic director Adriano Pedrosa introduce this year’s concept and saw the contributions of other artists, Agnes became even more convinced that her work would fit squarely within the exhibition.

Upon her return to Italy - she now works in New York- she realised the significance of being “foreigner everywhere”. She felt it especially when she confronted the pressure of Italian, a language strongly bound to gender in its grammar. Nonetheless, Agnes also underlines the beauty and strength found in embracing this feeling of foreignness.

In a past interview she gave to the magazine Speciwomen, she talked about her desire to subvert the power dynamic in the doctor-patient relationship. Therefore, I ask her if she had a similar target in mind when she created «Cyber-Teratology Operation».

She admits that there is a subversion in this sense, however this becomes clear because in this work the alien patient is also “its own apparatus”, it is its own doctor, in a way. This happens because Agnes believes that “it is very hard to separate ourselves from surveillance and the medical apparatus, because it is what defines us”. However, we need to become aware of this and gain agency over it.

Even though the creature is in a vulnerable position, this can also be a starting point for positive transformation. Or, as eloquently she puts it, “being a patient is being in transit, waiting for a transformation”.

Agnes claims that she wants to provoke spectators - her works are not about the future, they are about the present, because we are already under surveillance, subjected to medical scrutiny, under constant transformation.

I was also curious to know how Agnes thinks her work might be received by a casual spectator visiting the Biennale. To this she responds that, even though she is very dedicated to researching and writing about the theory behind her work, her artworks are still very “consumable”, very accessible to viewers. This accessibility is related to how her works take shape: in her own words, her artworks, though alien-looking, still maintain a “pop” sensibility.

As a final thought, just like with Frieda, I ask Agnes about her university studies and what kind of advice she might give to recent graduates who want to start a career in the artworld. She makes clear that it is important to choose the right degree path, without rushing the decision. This is key also because the artworld, as Agnes reminds me, has its own language requirements and being able to “speak it” proficiently is essential to comprehending what happens in it.

It is quite clear that Biennale 2024 includes plenty of queer artists who, with varying intentions and artistic means, are trying to carve a space for queerness to be visible. Rather than drawing conclusions, however, I am reminded again of Butler’s insight about how including voices that are usually marginalised - such as those of Indigenous, non-European, non-white, queer people and more - runs the risk of “re-colonising” those subjects who stand firmly outside the (patriarchal, capitalist) establishment.

Given what an institution like the Biennale represents, this gesture of welcoming voices from the margin, may simultaneously lead to an erasure of differences and a silencing of dissenting opinions. At the same time, perpetuating exclusions and discrimination - and this is something that Butler also points out - is certainly not the road to be followed.

What happens when artists participate in exhibitions that, perhaps up to a decade ago, would have found it difficult to open their doors to “foreigners”? Is it a betrayal, an acceptance of a compromise? Or is it a sign that times have finally changed?

Personally, I can give no definitive answers, but viewers who visit this Biennale can decide for themselves whether these “foreign”, “Other” artworks can steal at least a little bit of spotlight away from already-established artists and movements.

Share the post: