Liverpool Biennial 2023

The city of Liverpool was at the epicentre of the transatlantic slave trade for over one hundred years, surpassing Bristol and London as the slave-trading capitals in Britain by the 1740s, and much of the city was built through wealth generated by the trade of goods and people. Shipments arrived at the city’s docks from Brazil, India, the Middle East and, frequently, from the port city of Charleston in the US state of South Carolina. The cotton had been handpicked by plantation slaves whose ancestors had survived the boats from Africa. Stanley Docks once stored tobacco imported from West Africa and the Caribbean, earning Liverpool its title as the British Empire's second city. The trade made Liverpool, briefly, one of the richest ports in the world. Liverpool's history as a city built off the slave trade is not easily forgotten. The United Kingdom and the world are finally addressing the reality of the slave trade, and the art world has played a part in this, mainly through artists tackling this subject with its continuing ripple effect on our society. All art in the biennale has a connection to the triangle of Africa-The Americas-Europe.

The main statement and message about the event on its website say: “The 12th edition of Liverpool Biennial ‘uMoya: The sacred Return of Lost Things’ addresses the history and temperament of the city of Liverpool and is a call for ancestral and indigenous forms of knowledge, wisdom and healing. In the isiZulu language, ‘uMoya’ means spirit, breath, air, climate and wind. The festival explores the ways in which people and objects have the potential to manifest power as they move across the world, while acknowledging the continued losses of the past. It draws a line from the ongoing catastrophes caused by colonialism towards an insistence on being truly alive.”

More than 30 international artists and collectives have been invited to engage with ‘uMoya’ as a compass, divine intervention, and thoroughfare. Taking over historic buildings, unexpected spaces and art galleries, a programme of free exhibitions, performances, screenings, community events, learning activities and fringe events unfolds over 14 weeks, shining a light on the city’s vibrant cultural scene.

Liverpool Biennial 2023 is curated by Khanyisile Mbongwa, but its’ visual identity designed by Thom Isom.

Khanyisile Mbongwa is a Cape Town-based independent curator, award-winning artist and sociologist who engages with her curatorial practice as Curing & Care, using the creative to instigate spaces for emancipatory practices, joy and play. Mbongwa is the curator of Puncture Points, founding member and curator of Twenty Journey and former Executive Director of Handspring Trust Puppets. She is one of the founding members of arts collective Gugulective, Vasiki Creative Citizens and WOC poetry collective Rioters in Session. Mbongwa was a Mellon Foundation Fellow at the Institute of Creative Arts at the University of Cape Town, where she completed her masters in Interdisciplinary Arts, Public Art and the Public Sphere, and has worked locally and internationally. She is also currently a PhD candidate at UCT where her work focuses on spatiality, radical black self-love and imagination, and black futurity. Formerly Chief Curator of the 2020 Stellenbosch Triennale, her other recent projects include: Process as Resistance, Resilience & Regeneration – a group exhibition co-curated with Julia Haarmann honoring a decade of CAT Cologne (2020), Athi-Patra Ruga’s solo at Norval Foundation titled iiNyanka Zonyaka (2020) and a group exhibition titled History’s Footnote: On Love & Freedom at Marres, House for Contemporary Culture in Maastricht, Netherlands (2021).

Despite seeking answers in indigenous forms of knowledge, healing, and climate change, the central subject to the curatorial work in this year’s Liverpool Biennial is slavery or the impact of colonialism.

Also, after walking along Liverpool’s docks, Khanyisile Mbongwa went for a choice that reflects the curator's commitment to engage the city and its locality. Mbongwa calls it, how to be 'truly alive' despite colonial 'catastrophes'. After meeting local communities, especially as Europe’s oldest Black communities exist in Liverpool, the curator has chosen artists reflecting on this side of the city, too. Khanyisile Mbongwa has been working hard on stressing the past impact on today’s life and highlighting that Liverpool was once the British centre of trade and slavery. Unfortunately, at the end of the biennale, there are two questions still left unanswered. After all that has happened, where are we now? And, consequently, where do we go from there? Perhaps those are questions for us to think about now, aided with knowledge of the city’s history.

Liverpool’s Biennale include spaces around the city relating to the slave, tobacco and cotton trade – the Cotton Exchange, a Tobacco Warehouse, Stanley Docks, Princess Docks, Albert Docks and a selection of Liverpool’s great art venues such as The Bluecoat, World Museum, Open Eye Gallery, Victoria Gallery & Museum, FACT and Tate Liverpool.

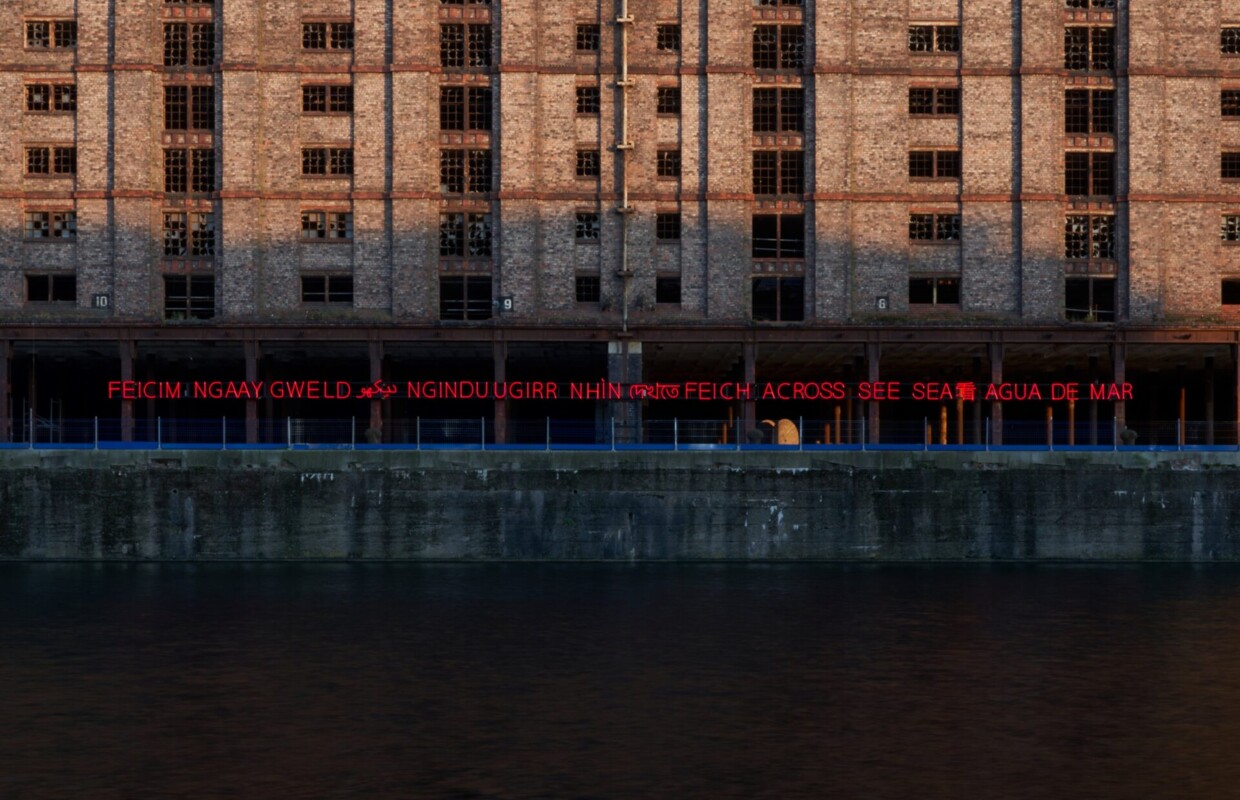

In Tobacco Warehouse - the largest brick warehouse in the world, Isa do Rosário paints tiny black figures on fabric to memorialise bodies lost to the sea. Further along the waterfront, only the hulking Tobacco Warehouse could do justice to Binta Diaw’s Chorus of Soil (2020), a reproduction of a slave ship made in mud. 130 sprouting shoots grow from its surfaces, one for each person killed in the 1791 Zong Massacre by British slavers. In the next room fact and fiction blur in Melanie Manchot’s docudrama STEPHEN (2023), where members of the Liverpool addiction and trauma recovery community speak out their stories. Melanie Manchot’s film is one of the few moments where the exhibition deals with Liverpool’s contemporary issues. Using professional actors and people in the local recovery community, Manchot’s work STEPHEN (2023) explores mental health and addiction in the city through the series of works which culminate in an hour-long final piece. Outside of Tobacco Warehouse, Brook Andrew presents a new large-scale neon work, entitled NGAAY (2023) (Wiradjuri word meaning ‘to see’). Combining languages including Irish, Scottish Gaelic, isiXhosa, Wiradjuri, Urdu, Mandarin and Welsh, the commission symbolises the cultural and historical linguistic diversity of Merseyside. It is at once a celebration and a critical examination of this diversity, highlighting its origins in the city’s history of trade in goods and enslaved people. These duplicate monikers serve as reminders of the British colonial exploits that spanned the globe. Through centring indigenous language and perspectives, Andrew’s work questions the limitations imposed by colonial power structures, historical amnesia, and stereotyping.

Another location chosen by Mbongwa that speaks directly to slavery is the Cotton Exchange – the place where the products of forced labour were once traded freely. Shannon Alonzo’s site-specific mural of charcoal and paint, entitled Mangroves (2023), explores the Caribbean Carnival’s relationship to space. Carnival celebrations exist globally to resist racial injustice and institutionalised oppression, offering a space for people of the Caribbean diaspora to assert their right to joy, self-articulation, agency, and ancestral legacy. Alonzo’s ritual of erasing and redrawing the mural partway through the exhibition is an offering to catalyse healing and a restoration of balance. But in Songs to Earth, Songs to Seeds (2022), presented at Cotton Exchange by Sepideh Rahaa portrays the often invisible and inaccessible process of rice cultivation in the paddy lands of Mazandaran, Northern Iran. The crop is both a container for indigenous forms of knowledge and, as a global food staple, is enmeshed within cycles of consumption, neo-colonial food politics and environmental injustice.

At Tate Liverpool, which is built on the city’s marina and the UK’s first commercial wet dock, completed in the early 18th century, the works of 11 artists focus on the past catastrophes. A particular highlight is Guadalupe Maravilla’s Disease Thrower (2019) series – two towering sculptures that double as headdresses. They are made from steel, gong, wood, cotton, glue, plastic, loofah and found objects Maravilla collected when he retraced his migration route from El Salvador to the US, having originally arrived alone aged eight to escape civil war. In his mid-30s, Maravilla was diagnosed with colon cancer, so in among the natural hues of wood, feathers and cotton, are brightly coloured plastic anatomical replicas. The artworks are used in healing rituals centred on non-western, alternative medicines. In this way, the artist transforms his trauma into empowerment.

Have we learned to tend to the wound?’ is the question posed in the back room of Tate Liverpool by Khanyisile Mbongwa. Her practice is deeply informed by her spiritual vocation as a ‘sangoma’, a type of indigenous healer – and the wound is everywhere in contemporary Liverpool. Torkwase Dyson’s abstract work Liquid a Place (2021) on Tate Liverpool’s ground floor is stricken by grief, where Torkwase Dyson’s curved charcoal structures – one half metallically smooth, the other rugged like plaster, both shaped like the hull of a boat – stand heavy as tombstones; haunting stories of cruelty and survival sit alongside offerings to spirits lost at the sea.

Nolan Oswald Dennis’ work No conciliation is possible (working diagram) (2018 – ongoing), presented at Tate Liverpool, is next in their series of installations consisting of map-like wall diagrams and a shifting selection of drawings and objects which amplify the diagrams’ contents. Dennis explores the hidden structures that determine the limits of our social and political imagination. But Francis Offman’s Untitled (2022) offers one such tale, a sea of books surrounding a bible the artist’s mother carried when fleeing the Rwandan Civil War, each tome precariously held by callipers – the tool used by Belgian colonisers to measure the facial features of Rwandans. This immense violence is juxtaposed against the daily pleasure of drinking coffee – a major export of Rwanda – with repurposed grounds spread on the fabric and covering the books. The dialogue between these objects demonstrates how personal experience is central to collective histories and healing.

In St Nicholas’ church gardens, Ranti Bam’s clay sculptures Ifas (2023) mark the burial site of the city’s first Black resident and former slave, Abell. The artist proposes clay as a medium for understanding human’s inseparability from our environment. The title ‘Ifa’ references the Yoruba word ‘I-fàá’, meaning ‘to pull close’, as well as ‘Ifá’, the Yoruba system of divination – Yoruba are one of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria, concentrated in the southwestern part of the country. The sculpted stools, known as ‘Akpoti’ are integral to indigenous life and are used for rest, care, communication, and communal gatherings.

The unnerving sensation of being watched can be found and felt in Nicholas Galanin’s series of masks Threat Return (2023) in St John’s Gardens. Seven upturned baskets with eyes and mouths stand on plinths echoing the monuments in the surrounding area, many of which honour those who made their wealth in the shipping trade. The eyes of Galanin’s faces find them and hold them to account.

The monumental work by artist Alicja Biala addresses the urgent issue of the impact of climate change on Merseyside, and is open to the public at St Nicholas Place, Princes Dock. Commissioned by Liverpool Biennial in partnership with Liverpool BID Company, the work, part of Biala’s Totemy (2023) series and formed of three totems, brings together statistics around climate change aiming to visualise the issues Merseyside faces in terms of rising sea levels and flooding by situating them using local examples. Each 4.5m totem features 3 ribbon flags pointing to three areas of Merseyside threatened by rising sea levels: Liverpool City Centre, Formby and Birkenhead. The flags reference international maritime signals, an alphabet of phrases used by ships around the world to communicate with one another. Visitors can digitally interact with each totem via the QR codes at the base of the sculptures to access information on the data that determines its proportions, gathered by the artist and researchers Jason Kirby and Timothy Lane from Liverpool John Moores University. The data represented shows what Merseyside could look like in the year 2080 if ice caps continue to melt and sea levels continue to rise at their current speed. Children in the region will be around retirement age in 2080, meaning that they will experience these effects of climate change within their lifetimes.

At Victoria Gallery & Museum artists Antonio Obá, Charmaine Watkiss and Gala Porras-Kim explore ancestral memory and contemporary experience. Their works offer spaces to rest, reflect and listen. Through these almost spiritual works, the artists invite us to engage with archives and collective memories. Brazilian artist Antonio Obá’s Jardim (2022), meaning Garden in Portuguese, is a large-scale installation consisting of hundreds of brass bells. London-based Charmaine Watkiss’ work forms what she called ‘memory stories’, visual representations of her research into the African Caribbean diaspora mapped onto life-size figures. Colombian-born Gala Porras-Kim, now based in Los Angeles, has created intricate drawings which imagine objects created from ancient vessels.

At FACT, Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński’s Respire (Liverpool) (2023) comes up with a suggestion to deal with the burden of the past, and it involves breathing. In a dark room, large projections feature participants from Liverpool blowing up a bright balloon. The artwork references the precarity of Black breathing and proposes breath as a means of individual and collective liberation. The colours of the balloons (red, black, and green) are reminders of the liberatory resistance struggles of the African diaspora, and for Black freedom in general.

Suspended in the centre of Open Eye Gallery, Sandra Suubi’s Samba Gown (2021) is a statement of resistance. The work, originally devised as a performance piece, imagines and re-enacts the Ugandan independence ceremony of 1962 as a wedding ceremony. A procession in the Samba Gown is used as a metaphor for what happened that day when Uganda (bride) entered a binding contract with its former colonisers (groom). The work draws attention to the transactional relationship that exists between former colonies and their colonisers. Comprised from plastic waste, the gown comments on plastic pollution as one of the major aftermaths of colonialism – Uganda receives thousands of tonnes of plastic waste from wealthy nations each year. Suubi evokes historical narratives, contemporary narratives on dumping grounds and the West’s exporting of waste, alongside contemporary forms of Western extraction such as knowledge and anthropological studies.

Bluecoat opens with a video work by Galanin where the narrator tells a child “I love you” and “You’re doing such a good job”. Presented in the Lingít language, spoken by the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific north-west coast of North America, the heart-warming film shows the child glowing under the compliments and celebrates marginalised languages. Kent Chan’s Hot House (2020 – ongoing) is an installation and project space which questions the relationship between climates and cultures, and the influence of heat and humidity on our bodies and minds. For Liverpool Biennial 2023, Chan engages with artworks and artefacts of tropical provenance from the Global Cultures collections of World Museum.

Kent Chan’s film delves into the archives of the World Museum, imagining a dialogue between works of tropical provenance from the global cultures collection. The pieces bicker over the difference between being an artefact and artwork. It is amusing, but also raises valid questions about the storage and ownership of works from other countries in the museums.

Share the post: