LOOP Fair: at the forefront of video art

Conversation with Gabriela Galcerán, the director of LOOP Fair

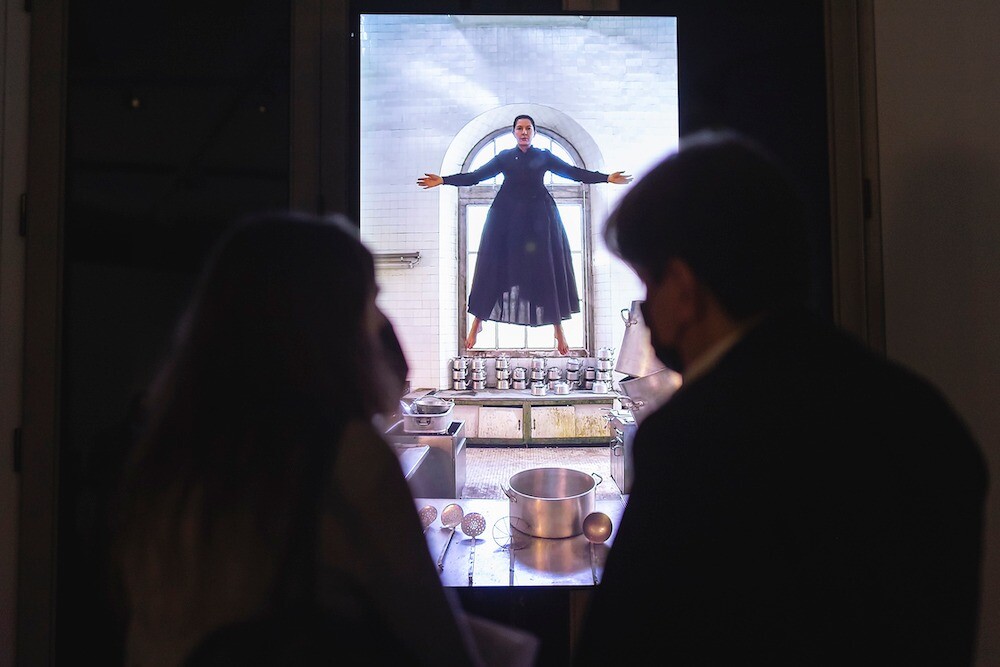

LOOP is an international platform with a team that has been working towards promoting video art since its inception in 2003, based in Barcelona, Spain. With annual events like LOOP Fair, LOOP Festival and LOOP Studies the organization is recognized wildly for bringing together artists, collectors, and industry experts with the goal of showcasing, celebrating, and educating audiences on film and video in contemporary art.

The next edition of LOOP Fair will be held from 21st til 23rd of November 2023 in the Almanac Hotel in Barcelona.

Madara: Please share a bit about yourself and about your role in LOOP, how you started.

Gabriela: LOOP is very dear to me and I have always been associated with it in one way or another. My first collaboration with LOOP was in 2008, when we launched a program called LOOP Diverse. We exhibited video art in a specific area of Barcelona known as El Raval, home to many immigrants. We placed video works in public places—for example, Pakistani artists showing in a Pakistani restaurant and Filipino artists exhibiting in spaces familiar to them. It was a beautiful program that was so successful we continued it the following year on a much wider scale. This was my first experience with them. Another factor is my passion for video art—I always attend the fair and have participated in various collaborations, and this year I am running the fair. I've always been in LOOP's orbit, always connected.

LOOP as a platform was created in 2003, can you share what was the driving force behind the start of LOOP?

LOOP, as a platform and an art fair, was born out of the necessity to respond to artists working with the moving image.

The founders realized that in traditional fairs, it's very difficult to view video, as it requires a lot of attention and engagement. They came up with the idea of doing a fair dedicated to the moving image and to hold it in a hotel. The decision to use a hotel initially came from economic reasons because the moving image is a very niche sector and the market is not that big. They thought, "Okay, if we do it in a hotel, maybe the galleries can use the same room to also sleep in." And now, this unique approach that is specific to LOOP has become the DNA of the fair, creating a very immersive and cohesive atmosphere. When galleries, VIPs, and collectors all stay in the same hotel, it creates a boutique feel to the event. The conversations you overhear in the corridors, by the bar, and in the restaurant are all about video. These discussions are further enriched by the talks and professional meetings that occur during the fair. For several days, the hotel is packed with people all focused on video art. So, that's how it started. We also run a city festival that starts the week before the fair. It's a way of engaging with the city and presenting a more open view on how to experience this type of art.

So LOOP has always been international?

Yes, from the very beginning. The sector of video art is as small as it is; you need to be international. And one of the special things about LOOP, what sets it apart from other fairs, is that we focus a lot on video collecting. Obviously, the artist is at the center of our work, but we do approach the fair from the viewpoint of a collector. We try to support collectors and to foster an environment in which they can connect and exchange ideas because the person who collects video is a very particular type of collector.

Video collecting is quite peculiar from the perspective of more "traditional" fine art collecting. Everyone, collector or not, knows the obvious thing to do with an acquired painting: you put it on a wall. For many, the act of collecting video art seems mystical. What does it mean to be a collector of video art?

You're very right in your analysis, and I'd like to point you to a publication we did with Mousse Publishing. It's titled "I Have a Friend Who Knows Someone Who Bought a Video, Once". It compiles interviews and profiles of video collectors and artists, like Erick Beltrán, Marc and Josée Gensollen, Sandra Terdjman, Haro Cumbusyan, and others. The conversation with Haro was particularly interesting. He said that one collects video art not only as an intellectual endeavour but also to be part of a special club.

Video collectors often go beyond merely collecting; they engage actively, a level of engagement you might not find with other art forms.

Some collectors assume the role of a producer and frequently lend works from their collections to institutions. An example is the Han Nefkens Foundation. Han Nefkens collaborates with video partner organizations worldwide, including LOOP, and together we co-produce videos. Thus, the sense of ownership over a video is more diffuse.

Collecting video isn't straightforward because it isn't a physical object but a bundle of rights, and it can come with technical challenges, requiring the right equipment to display it.

There are clear do's and don'ts for each work, rules on how to archive it, etc. That's why, some time ago, LOOP created a simple yet clear contract for transacting video art called the LOOP Protocol. It can be downloaded for free from our website. Video collecting can be complicated; first-time collectors might be unsure about what they are receiving. Is it the file? The monitor? A video collector is typically very engaged, thoughtful about where the piece is shown, and in partnership with whom. They are individuals willing to do more than just make the purchase.

So would you say that the act of collecting video art demands for the piece to be shared? This seems in line with the history of the video medium, which is about making the moving image more accessible compared to shooting on film.

Yes, I would say so. These collectors often are very willing to share their collections in various ways. Take Julia Stoschek, for instance, who invests considerable time, energy, and resources into making her collection publicly accessible. Then there’s Shane Akeroyd, who offers his collection online. Another approach is exemplified by Han Nefkens, whom I've already mentioned. Han doesn’t keep the files himself; instead, he places them in museums and other institutions. His foundation is particularly active in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. So, yes, I believe sharing is inherent to the DNA of a video art collector, aiming for a very open viewing experience.

This all suggests that the format of the LOOP fair is significantly different from other fine art fairs. Could you share how you see LOOP interacting with other art fairs around the world?

Video art does have a relatively small community, and within this community, we are always in contact with each other. As for participating in larger, more mainstream events, it's quite challenging because of the nature of the moving image. A few years back, we collaborated with artgenève, where they hosted a separate section for LOOP. We're always open to collaboration, but it's not easy to implement, since video demands a different level of engagement compared to traditional artworks. It's a challenge to alter the rhythm of visitors who are accustomed to viewing paintings.

Do you think that at a fair that focuses on art on canvas, having “something that moves” can sometimes be used as an eye-catcher?

Ah, that's an interesting question. Yes, I'm sure that there is an element of “being cute” about it, yes.

Obviously, LOOP has taken on a sort of caretaker role for the representation and evolution of video art in your region. What is the current aim that your team is striving for?

G: At the end of the day, the artist is at the center of everything we do, whether it's the LOOP festival, fair, or any other project. So whatever we can do to support artists and their production, that is the way we will go. We’ve been involved in co-producing works with partners, and we offer a production grant alongside Han Nefkens. We also have a Europe-wide production grant called “A Place”, producing one work per year. So, I would say increasing our activity in the field of production is a goal for us. And perhaps, one day, we might even take LOOP to other locations. Who knows?

What would you say is needed for video art to reach new heights both regionally and internationally?

This is a great question, I wish I had a straightforward answer.

I think that because of the difficulty of the medium, sometimes these kind of projects get left behind when it comes to public funding. In this regard, we are still considered the ugly duckling.

Changing this perception is one of LOOP's objectives. And, we need to make video more accessible. Perhaps we should make people talk about video as much as they talk about photography or paintings that they've seen. It should be incorporated into the everyday language, and this can be done with institutional support, and more presence in the media.

We see that art fairs worldwide are working towards becoming more accessible, creating an environment where anyone, even a passerby, can participate and feel included, not just collectors. Is this true for LOOP as well, or would you say that the visitors to the LOOP fair are as niche as the medium itself?

I think that the majority of our visitors are people who know where they are going, but that doesn’t mean that we don’t make a very big effort to open up to different audiences. We have a team that is working on attracting new audiences and organizing guided tours for them. We do what we can to open up and make the experience less intimidating. We don’t want to just open the doors and then say, “You’re on your own now,” no. We want to give a bit of context, and make them feel like they belong, like this fair is not just for some crazy weirdos. And I must say, this work is really rewarding.

The next edition of LOOP fair is in a few weeks already. If I would ask you highlight something from the programme, what would it be? What are you especially looking forward to?

Personally, I'm really excited to welcome Esther Schipper Gallery, which will represent the video work of Ugo Rondinone, especially since he does not often work with video. We will also welcome Lawrence Lek, who has had major shows recently – earlier this year in Seoul at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, this summer at the Stoschek Foundation, and he has also just opened a massive show in Berlin at the LAS Art Foundation. He will be showing one of his pieces with the gallery Sadie Coles HQ from London, which will mark their first time at the fair. With their work, they support video art, and it's important and exciting for us to have them. Additionally, we are always very welcoming towards local galleries from Spain, because we want to foster and create strong networks.

While looking back at the 20 years behind LOOP, any thoughts and hopes for what's yet to come?

I would wish for LOOP to be busy the whole year, to have fairs happening in each continent. I would like to develop an emerging artist section and devote a lot of money to support new creations. We can dream big! But it does come with lots of challenges.

Time-based art is moving and developing so fast, that we always have to be quick on our feet, always alert and never lose focus on doing what we do with the goal to support the artist and their creation.

This has to be at the core of what we're doing not only this year but also in the next 10 years to come.

Share the post: