Preservation vs. Profit: How the Battle for Cultural Heritage Plays Out in the Auction World

Imagine the excitement in the art world when a painting by a renowned Old Master unexpectedly reappears at auction. These moments are not just about the monetary value of the artwork itself, but also about the history and cultural significance that it carries. When pieces of national importance resurface, they often capture the attention of government officials and cultural heritage advocates, who may see them as pivotal to preserving a nation's identity.

The auction that followed would be more than just a sale. It would become a battleground where cultural heritage policies clashed with market dynamics. Such cases underscore the ongoing tension between the state's commitment to safeguarding cultural heritage and the art market's drive for profit and private ownership.

Interactions between cultural heritage policies and the art market are common. In the past few years, there have been a few high-profile cases in various countries where paintings of potential national importance were auctioned or associated with major auction houses. Each of these instances tells a story of negotiation, legal battles, and sometimes, heart-wrenching decisions as governments and auction houses grapple with their respective roles.

Unexpected Caravaggio Epic in Spain

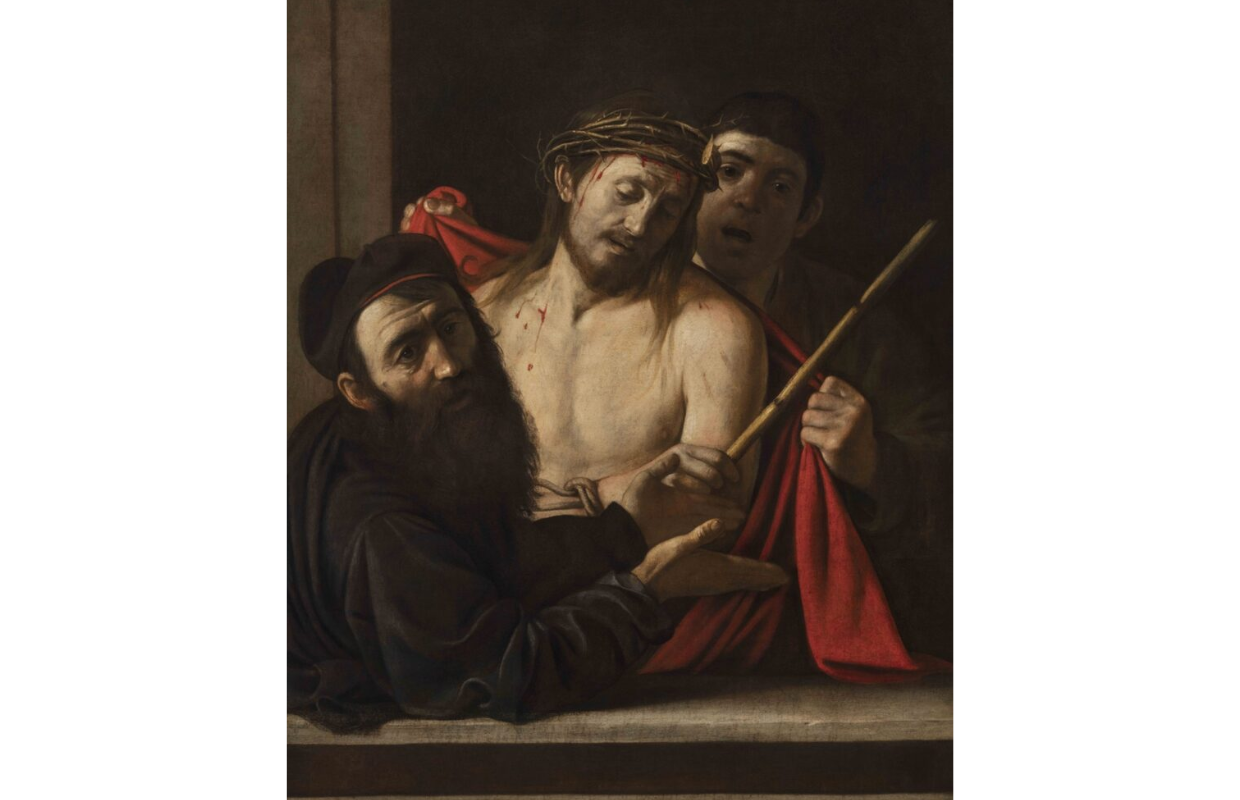

It is not every day that an old painting brought to an auction house turns out to be a work of an Old Master. This is what happened to a lost masterpiece by Caravaggio (Italian, 1571-1610), the legendary Baroque painter whose dramatic use of light and shadow has captivated art enthusiasts for centuries. The work in question, titled 'Ecce Homo,' became a focal point of intrigue, partly due to the heated debate over whether it was indeed painted by Caravaggio himself.

According to the Prado Museum and The Art Newspaper, the painting's journey is steeped in Spanish art history. Between 1821 and 1823, the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando made a trade with Evaristo Pérez de Castro, a Spanish diplomat and honorary Academy member. In exchange for a work by Alonso Cano, the Academy handed over 'Ecce Homo,' which remained in de Castro’s family for generations. The painting, with its storied past, surfaced unexpectedly at the Madrid auction house Ansorena in 2021.

Initially, the painting was listed in the auction catalog under the modest title 'Crowning of Thorns,' attributed to the 'circle of José de Ribera,' and valued at just €1,500. It was almost as if history had overlooked it. However, experts from the Prado Museum were struck by its resemblance to Caravaggio’s distinctive style.

The Spanish Ministry of Culture acted swiftly, stepping in to prevent the painting from being auctioned. The painting was removed from the bidding, and an international team took on the monumental task of restoring and authenticating it. The choice of Colnaghi, a renowned art gallery, for these tasks added a touch of prestige to the painting’s comeback story.

The speed of consensus around the work being a Caravaggio upon its rediscovery was absolutely unprecedented in the critical history of the painter [about whom] scholars have rarely agreed, at least in the last 40 years.

Once confirmed as a genuine Caravaggio, 'Ecce Homo' was sold to a new, undisclosed owner. Its temporary exhibition at the Prado in May 2024 was met with both admiration and skepticism. Some experts remain divided, their debates echoing the uncertainty that surrounded the painting's origins.

This case vividly illustrates the state's proactive stance in the Spanish art market. The quiet cooperation between Ansorena and the authorities, followed by the government’s direct involvement in the painting’s future, highlights the intricate dance between art, heritage, and cultural policy.

France’s Record-Breaking Balance

In 2023, the author of this article had the opportunity to see this magnificent painting in the Louvre when its fate was not yet completely clear. Jean-Simeon Chardin's (French, 1699-1779) 'The Basket of Wild Strawberries' stands out as one of the most cherished 18th-century French paintings used to be held in private hands. This piece is a testament to Chardin's mastery of still life, breaking away from the ornate Rococo styles that were all the rage during his time. The quiet elegance of a painting captures the simple beauty of wild strawberries, reflecting a shift towards more modest and contemplative art.

First showcased at the Paris Salon in 1761, 'The Basket of Wild Strawberries' became a part of the Marcille family collection. This collection boasted works by Chardin and other luminaries of French art, such as François Boucher and Jean Honoré Fragonard. The painting, however, faded from public view in the mid-19th century until its surprising reappearance at an Artcurial auction in March 2022.

The auction was a dramatic affair. The painting, initially valued €12-15 million, saw the bidding war escalate to an astonishing €20.5 million (with the final price including the buyer’s commission reaching €24 million). This not only set a new record for Chardin but also made waves in the art world, marking a historic benchmark for 18th-century French paintings at auction. The buzz in the room must have been electric as the bids soared.

Ultimately, the painting was bought by the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, known for its commitment to 'definitive excellence,' The acquisition of Chardin’s work would add a significant gem to their collection, reflecting the museum’s dedication to showcasing exceptional art.

Yet, the story didn’t end there. After the auction, the French government took decisive action. The Louvre Museum, with its finger on the pulse of cultural heritage, stepped in to repurchase the painting from Artcurial.

But this painting is worth waiting for, even if we consider the Louvre may finally obtain it. It’s a win-win in every sense as a public collection will acquire the work

Declaring it of cultural interest, the French Ministry of Culture imposed a 30-month export ban. This period allowed the Louvre to gather funds and integrate 'The Basket of Wild Strawberries' into its esteemed collection, ensuring it remained a treasure within France’s cultural heritage.

These cases illustrate differing impacts on the art market. While Chardin's painting had a clear market value at sale, the Caravaggio’s exact price remains shrouded in secrecy due to its private transaction. Such differences underscore how Spain and France navigate the complexities of cultural heritage and art market priorities in their unique ways.

The British Consensus

In British tax law, the Acceptance in Lieu (AiL) scheme offers a solution for settling inheritance tax debts: transferring the objects of national importance to state museums. Auction houses play a key role in this process, negotiating between the private owners and the state while earning fees for their consulting services.

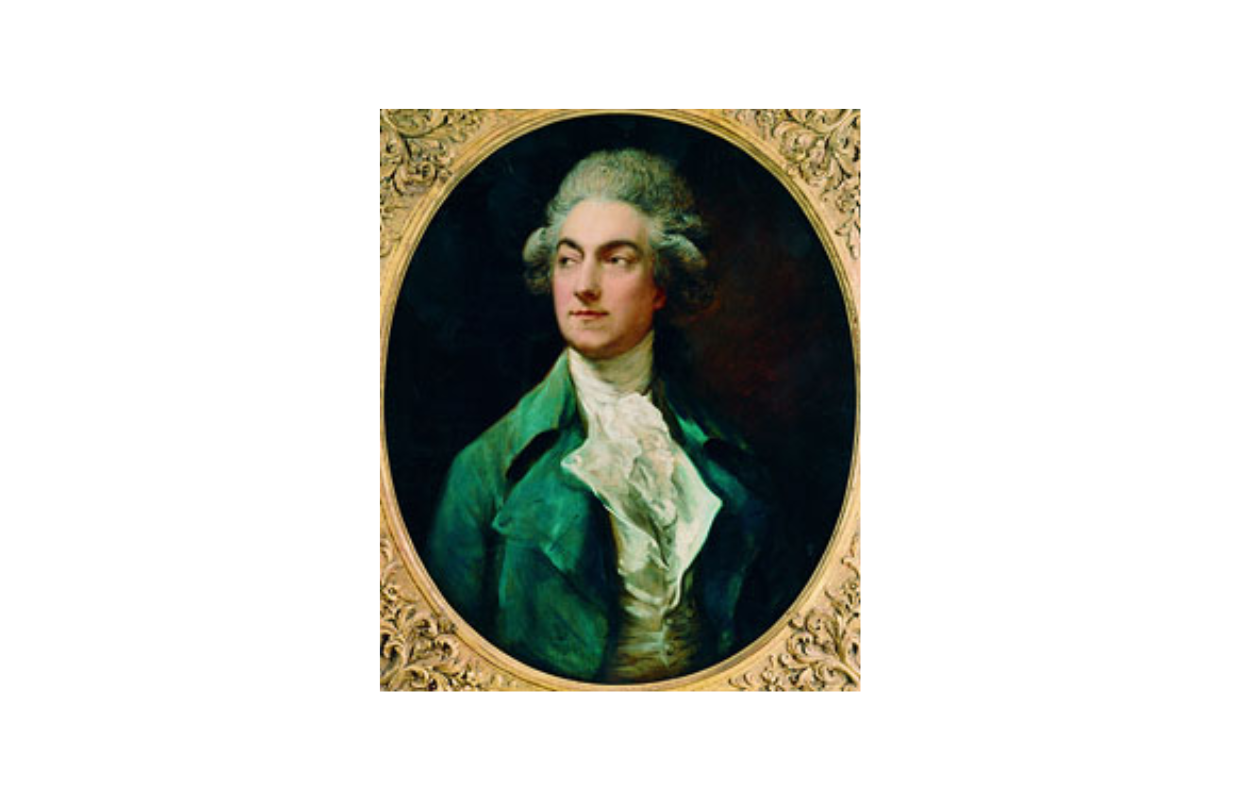

This scheme facilitated the acquisition of two Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727-1788) masterpieces by the National Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery from the private collection of George Pinto (1929-2018). Pinto, an avid art collector, amassed an impressive array of 17th and 18th-century works, emphasizing Gainsborough’s monumental role in British art.

One of the paintings, a portrait of Margaret Gainsborough, had a captivating history. Once thought lost, it resurfaced in the Pinto collection years later. In 2015, Dr. Lucy Peltz, Curator of 18th-century collections at the National Portrait Gallery, launched an ambitious search for Gainsborough's family portraits. She placed a notice in 'Country Life' magazine, hoping to unearth any hidden gems. The effort paid off when readers helped locate the missing portrait, leading to its display in the 'Gainsborough Family Album' exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery after Pinto's passing.

Another exquisite Gainsborough portrait, featuring the renowned 18th-century dancer Gaetan Apolline Balthazar Vestris, has its own rich history studied by Martin Postle. First documented in 1856 as part of Sir Robert Peel's collection, it was initially displayed among portraits of political figures:

By Gainsborough is a portrait of Vestris the dancing master – a charming study – ; it was in the collection of the late Sir Robert Peel at Drayton Manor, among his likenesses of statesmen, but was weeded out when verified as representing Vestris.

It later appeared at the Dudley Gallery and was acquired on June 22, 1867, from Mitchell by Cox. By 1905, collector Asher Wertheimer had added it to his collection, and it was first published in the Burlington Magazine that same year.

In this case, the state was involved from the start. The auction house played a crucial consulting role, persuading the government of the painting's national and artistic significance. This collaboration ensured that these priceless works by Gainsborough were preserved for public appreciation, demonstrating the vital interplay between private collections, auction houses, and state institutions in preserving cultural heritage.

Navigating Future Art Market and Heritage Issues

Laws on cultural heritage often make the prestige of auction houses and the size of the local art market less important. These laws focus on preserving national heritage over boosting the art market. However, the art market can still benefit from these deals, even if the state is involved.

Take the Caravaggio case in Spain, for example. This situation exemplifies Spain’s commitment to preserving cultural heritage rather than boosting the art market. Spanish laws require auction houses to alert the state about artworks that might have heritage value. This can lead to the state blocking their sale, which can impact the art market by preventing the establishment of a market price, particularly if the transaction remains private and isn’t reflected in Spain's global art market statistics.

In contrast, France balances between protecting cultural heritage and boosting the art market. French auction houses aren’t obligated to notify the state about artworks of significant cultural importance, which can lead to new record prices at auctions. Instead, France employs strict export rules. When an artwork is declared a national treasure, its export is banned, as seen with the Chardin still life. By designating the painting as a national treasure, France kept it within the country, allowing the auction to set a new price record, while simultaneously supporting its cultural policies. The excitement of setting a new record while preserving a national gem is a compelling story of balancing market forces with heritage protection.

In the UK, the AiL scheme reflects a different approach. Although this scheme doesn’t directly boost the British art market, it’s less of a concern due to London’s status as a major art hub, making the UK the third-largest art market globally. The state’s focus on preserving cultural heritage encourages cooperation between state institutions and art market professionals, ensuring national treasures are protected while maintaining a robust market. The behind-the-scenes negotiations and strategic decisions in the AiL process illustrate a collaborative effort to preserve and celebrate British art.

Looking ahead, the tension between protecting cultural heritage and profiting from the art market is unlikely to change much. Important paintings will continue to reappear, going up for auction and catching the state's attention. Some cases will attract more attention, others might become controversial, and some will see smoother negotiations.

Examining these three approaches, it seems that France’s model works best. It combines strict heritage laws with a dynamic art market, benefiting everyone involved. This model could serve as a guide for balancing market interests with cultural preservation, potentially offering a framework for resolving conflicts between auction houses and the state. Meanwhile, the UK demonstrates how a strong art market, coupled with specific heritage laws, can facilitate a harmonious relationship between state officials and art professionals, suggesting that a resolution between cultural preservation and market interests might be achievable in the future.

Share the post: