Who’s watching this? A visit at the Holy See Pavilion

Venice Biennale 2024

There has been considerable buzz about the choice of location for the Holy See Pavilion at this year’s Biennale in Venice. When it was first announced that its location was going to be the female prison on Giudecca island, this choice immediately generated significant interest due to the unusual nature of the venue for an art exhibition, let alone for the Biennale.

Titled ‘With my own eyes‘, this exhibition would like to reframe the way outsiders (i.e. anyone who is not incarcerated) looks at the detainees who live inside the prison walls. The title clearly indicates the idea of seeing (and thus thinking) independently and individually about the people who are imprisoned here, and possibly about the prejudice that might affect viewers' opinions.

The Holy See Pavilion puts the visitor in front of a difficult question: what is the point of view that frames these artworks and the guided tour as a whole? Why would these renowned contemporary artists agree to exhibit in a female-only detention centre? And, finally, why would the Vatican choose this venue as its pavilion?

Before visitors enter the prison, they can admire Maurizio Cattelan’s huge painting on the side of a chapel (right next to the detention centre) depicting a pair of dirty feet, probably a hint at other artworks like Mantegna’s ‘Cristo Morto‘ (1475-8) or Annibale Carracci’s ‘Cristo morto e strumenti della passione‘ (1583-5), or also at the ritual washing of feet done by Christ to his disciples. Cattelan’s painting is entirely in black and white, and its huge size brings back attention to these “lowly” body parts, in an act of re-evaluation of what society sees as “dirty” or indecent to look at.

Inside the prison, the guided tour is led by one of the prisoners, in my case, a young woman named Giulia. The choice of an internal, and consequently partial, guide is essential to this reframing operation that the pavilion appears to aim at. In fact, it seems inappropriate to call it a pavilion, as aside from the artworks on display, the prison locales do not seem to have been "cleaned up" for the Biennale.

As my visit happened on a particularly rainy and windswept day, this forced the tour to be re-routed and, consequently, visitors couldn’t see one of the two works by Claire Fontaine and also Simone Fattal’s work. The small group of visitors was led through totally functional corridors and rooms, where one could also notice some litter or general disorder. Essentially, it looks like a place where both the police-force and the inmates spend their days. An ordinary, slightly messy place. Except it's all far from ordinary, starting from the fact that viewers are not allowed to bring their phones with them, which means everyone must concentrate and possibly memorise what they are experiencing (another meaning underneath the Pavilion's title).

The first stop is in front of Claire Tabouret's paintings. All the canvases depict children, who are either the sons and daughters of the prisoners or are important in their lives even though not blood-related. Giulia tells the small crowd that Tabouret was at first sent photographs directly from the inmates and then visited the prison and detainees herself. Giulia also informs the viewers that one of the pictures portrays her partner's daughter.

Particularly striking is a portrait of three children standing before an altar where a crucified Christ figure stands on display (here and throughout the visit, the connection to religion and the Vatican are subtly reinforced). All the paintings have the children staring directly at the viewer, a direct address that fits squarely with the Pavilion's intended message. While the emotional impact these pictures are meant to have is quite evident, as the children depicted have a clear connection to the detainees in the prison, it may also feel a bit “exploitative” of the children themselves. Far from wanting to sound utterly insensitive, I still feel some ambivalence about this kind of representation. Are the children really meant to be exhibited in this way, in order to leverage the viewers’ empathy towards the imprisoned women?

The following point of interest is in a small deconsecrated chapel next to the room that contains Tabouret’s paintings. In the chapel the visitors can look up at the ceiling to admire Sonia Gomes’ coloured sculptures which take the shape of ropes hanging from above. These ropes have some thicker, cocoon-like parts, made of various materials, which our guide sees as larvae that are about to hatch and give birth to beautiful butterflies. Gomes’ sculptures have an entrancing quality, as they rotate slightly suspended in the air, an interesting effect which, together with an emotional letter written by the prisoners and read to us by Giulia, creates an intense atmosphere and is perhaps the highpoint of the entire visit.

The visit proceeds through the cafeteria, where artist-nun Corita Kent’s Pop-Art inspired artworks are displayed. Again, it is interesting to see how the works of a well-known artist are exhibited in a totally ordinary and even slightly drab room. The artworks shown here are colourful paintings or prints which often bear some simply written phrases: one can admire renowned works such as ‘E Eye Love‘ (1968) or the screenprint ‘the juiciest tomato of all‘ (1964), which echoes Andy Warhol’s infamous Campbell’s Soup Cans.

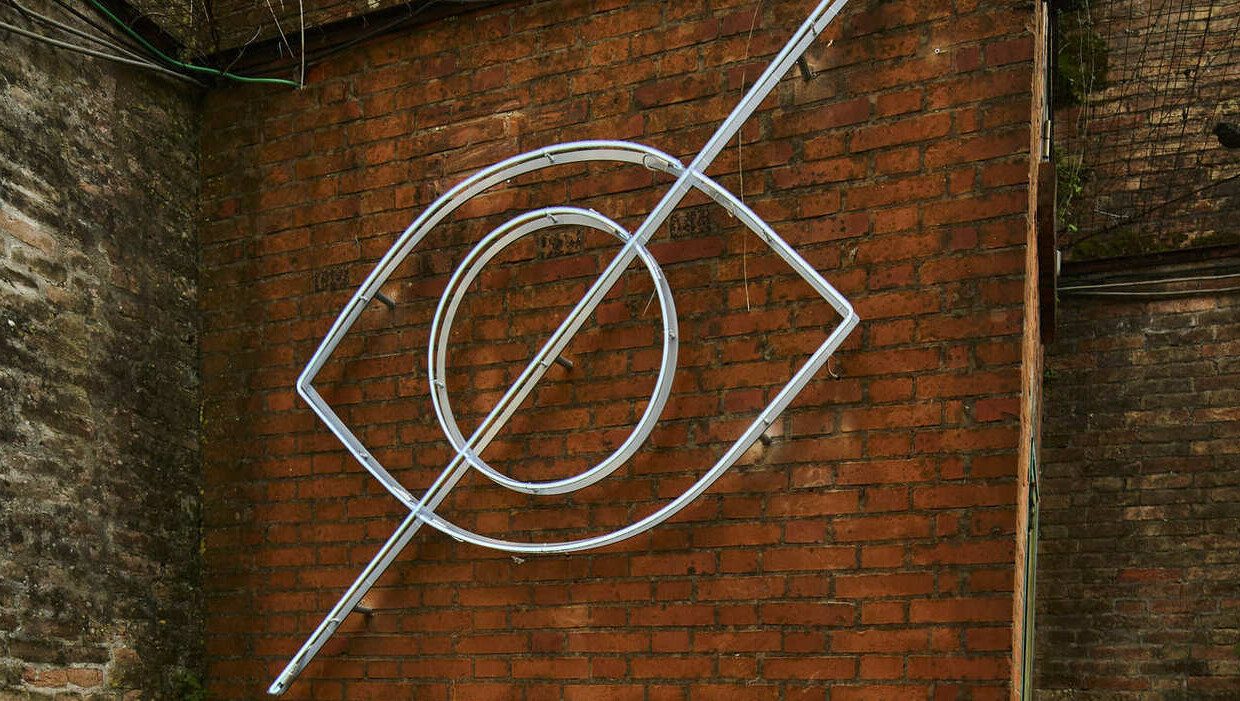

Of the two artworks by duo Claire Fontaine, only ‘Siamo con voi nella notte/We are with you in the night’ is visible to us (the other work being probably in a place where it would have been hard to stand due to the rain and wind). This one is a blue neon writing attached to a building which faces onto a courtyard, probably where the detainees spend some of their free time. Giulia explains that the neon writing indicates that the artists are thinking about the prisoners, even at night, when they cannot be with them. What is more, our guide recounts that at night the artwork’s neon illuminates the women’s cells directly across from it, casting a glow into their confined spaces.

The final stop is in a small room where visitors are shown Marco Perego and Zoe Saldaña’s short film ‘Dovecote’ (2024). This film, entirely without dialogues, follows Saldaña’s character, a female prisoner who wakes up on the day she is finally going to be released from prison. Of course, viewers do not realise this until the very end, when Saldaña’s character leaves the prison building. Consequently, the teary hugs at the start of the film with other inmates suddenly make sense as hidden clues hinting at the finale.

While the film is well-intentioned, at times it felt like it was heavy-handed (especially in its musical score) and perhaps out of place. It made one question come to mind: why would a Hollywood actor like Saldaña enter a prison and take the leading role in a short film about a prisoner on her final day of confinement? Indeed, who is this film for? Is it for the prisoners themselves or is it for the people who are outside looking in?

After all, the whole exhibition risks becoming something akin to an ethnographic spectacle, with casual spectators looking in at these “Others”, these women who are imprisoned. The question about whose gaze these artworks want to satisfy comes back to haunt me right at the end of the guided tour.

This interrogative can be coupled with the one I mentioned at the start of this article, about the interest garnered around the unusual choice of this female prison as the venue for the Holy See Pavilion. The intention, according to Cardinal José Tolentino de Mendonça, was to “find new words, new visions of the world that can make justice for humanity”, with the help of contemporary art.

With regards to the Pavilion’s title, the Cardinal explains that, in our modern world, “seeing with your own eyes” confers to vision a unique status, one which makes us all witnesses, rather than passive spectators. He then compares religious experiences with artistic ones, because both always imply the full presence of a subject.

While it is clear that the necessity of coming closer to these prisoners is essential if one wants to even remotely understand their condition and how this impacts on their lives, there will always be a certain distance between how a “normal” person and an inmate spend their days. Can art truly bridge this gap and address this distance without silencing the voices of those who feel this separation most profoundly? Certainly, the flipside is that if we never try to approach those living completely different lives, there will never be a point of contact, which may be even worse.

However, what this exhibition still lacks is any reference to the prison system itself. This is not to say that all artists should have directly and bitterly criticised the penal institution ( though surely some do so indirectly). At times, it seems as though the artists (and the curators) have forgotten that what makes these women “Others” to those outside is precisely the institution that incarcerates them. And this is not really something that can go unnoticed.

While the decision for prisoner-guides not to disclose for which crimes they are imprisoned is intended to eradicate any possible prejudice visitors might hold if they knew these details, it is also a double-edged sword. This works precisely in favour of erasing the impact of the penal system on these women’s lives.

Perhaps the exhibition would have been more impactful had it encouraged visitors to face the crimes committed by these women and try to overcome them through an act of forgiveness (one of the Church’s cardinal values) that requires a genuine moral self-examination. By sweeping the crimes under the rug, it seems like a chance for deeper engagement and understanding is lost.

Nonetheless, regardless of personal opinions on the efficacy of the Holy See Pavilion as a whole, one thing is certain: attending this show implies a willingness to ask (oneself) questions that cannot leave the viewers unmarked. Otherwise, it means that we’re just looking at some pretty pictures on a wall and calling it a day.

Share the post: