Art and/as Commodity: Analysis of Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes

The mid-twentieth century represented a period of mass change for the United States, a nation reckoning with its emergent world status as a postwar hegemonic leader and the new center of the artistic world. With this status, thanks to the intellectual support of critics like Clement Greenberg and even covert international promotion by the CIA, the United States elevated the avant-garde, celebrating so-called advanced and sophisticated movements like Abstract Expressionism and New York School artists like Jackson Pollock. Inversely, this accompanied a disparagement of kitsch—the low-brow yet popular mass media—as the enemy of the avant-garde and a shallow form of non-art. However, the unprecedented dominance of the avant-garde turned this movement, which in its ethos strove to defy orthodoxy, into a new form of mainstream media in itself. This led artists in the 1960s to become increasingly experimental in their work. Where Abstract Expressionist artists enforced a sharp divide between the avant-garde and kitsch, the 1960s witnessed a transformation; more and more artists not only embraced kitsch but made it central to their artistic practice, operating not by separating fine art from popular culture but by working within the space between the two. This is strikingly apparent in Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, a series of sculptural Pop Art pieces that investigate the complex relationship between art and commodity through its formal presentation.

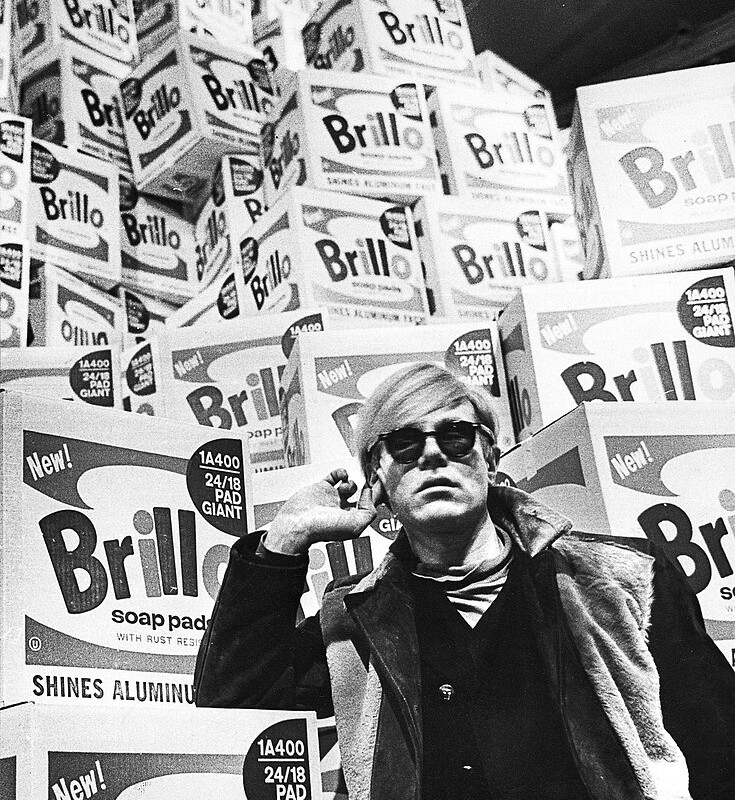

Following Warhol’s infamous series of Campbell soup cans, Brillo Boxes epitomizes his practice of replicating mass commodities and elevating them to the status of art. Perhaps the most infamous quality of Brillo Boxes’s artistic form and composition is the apparent lack of artistry involved—the plywood boxes are sized and painted to mimic the real branded soap pad boxes as closely as possible. In sharp contrast to preceding artists like Pollock, Warhol eliminated all aspects of gestural or autographic marks from his work. Each surface is painted boldly, flatly, and an exact replication of the commodity they are modeling, down to the trademark symbols, advertising slogans, and even relative sizing of the boxes. The boxes themselves are cheaply and impersonally made through screen-printed designs on plywood, reflecting the mass-production practices likely used on real Brillo box packaging. Another notable formal feature of this piece is the serial repetition of the boxes. Warhol made one hundred identical Brillo Boxes for exhibition, allowing them to be presented like any other mass-produced commodity for sale rather than a sculptural work in exhibition. This, paired with Warhol’s choice to make Brillo Boxes a sculptural replica of a real product rather than a painting of one like his previous work, enables Brillo Boxes to open often controversial dialogue about the relationship between art and commodity.

These artistic practices impart Warhol’s work with a commercial quality that embodies the very aspects of kitsch critics like Greenberg staunchly rejected, representing the transition of American art from Abstract Expressionism into Pop. Artists like Pollock, Newman, or Rothko emphasized the gestural and emotional aspects of art as non-representative, embodied experiences for the viewer, removed from the distractions of popular culture that crowded their everyday experiences.

By contrast, Warhol recognizes that consumerism is rampant in the United States and appropriates it into his artistic model. Unlike the bravado or intensity of Abstract Expressionism, Pop—named for its utilization of popular imagery—is quickly and easily perceived.

Viewing Pop is not a profound, embodied experience but a confrontation of a familiar image in a new, irreverent context. Items like the Brillo boxes were widely recognizable commodities, featured heavily in advertisements, and accessible products to the average American irrespective of class or demographic. These qualities, the epitome of kitsch, are also what made products like the Brillo boxes ideal for Warhol’s practice. He calls attention to the realities of the 1960s, a period increasingly occupied with mass media, popular culture, and new commodities competing for the public’s attention—a public that was becoming increasingly dissociated from this oversaturated reality. Warhol openly recognizes this disassociation, and his art—which forcefully inserts these marketed commodities onto the stage of fine art—thus reflects the national sentiment at the time in a way that better represents and is accessible to the whole of the American public. In many ways, Warhol’s choice of subject—soap pads, in this instance—not only turned these commodities into art but preserved them as artifacts of his time that spoke to the habits of ordinary people.

Moreover, the seriality and repetitive nature of Warhol’s Brillo Boxes opens the work to a broader conversation on the nature of consumerism and capitalist culture that dominated the American landscape. In the 1960s, the United States enjoyed its new privilege as not just the artistic but economic center of the postwar world due to international policies like the Marshall Plan and neocolonial interventions in Latin America and Southeast Asia. Furthermore, Cold War tensions with the communist Soviet Union pushed the United States to not only wholly embrace, but exalt its status as a democratic capitalist nation, advocating for the so-called freedom that came from their economic model in the competition to maintain global hegemony. The ramifications of these broad historical contexts were felt on a domestic scale. Mass production became increasingly common, as did the advertising and media technology used to introduce these goods to more and more American households. The familiarity of images such as the Brillo box adds to their complexity when presented in a new, artistic light. Yet, the repetitive nature in which Brillo Boxes would have been viewed, in which dozens of identical boxes were stacked and presented together without any regard to creating an artistic arrangement, eliminates any sense of individuality within or reverence of the boxes to the audience. While crafted copies, these boxes are not special, not distinct from the product they represent.

They are just that: copies, meant to be visually consumed in the same way as their purchasable counterpart. In this way, the repetition calls attention to the overbearing experience of being a consumer in 1960s America, continually exposed to louder colors declaring yet another “New!” (as labeled on the side of Brillo Boxes) product demanding one’s attention and more importantly, money. At the same time, the seriality of these identical forms desensitizes the viewer to the details, replicating the experience of someone walking through a store aisle or a mass-production factory floor.

While Warhol often eluded clear statements on his intentions or purpose for his work, even fashioning his public persona to be purposefully enigmatic and aloof, it is clear that his work investigates the relationship between art and commodity.

More specifically, Warhol’s Brillo Boxes expands this conversation to explore the role of art as a commodity in itself. While Warhol’s other works play with repetition and consumerism, from screenprints of mass media photography to iconic celebrity figures, to a series on Campbell soup cans, Brillo Boxes is distinctive through its sculptural, rather than painterly, form. Brillo Boxes is intensely provocative because, unlike a painting of a popular commodity, they are visually indistinguishable from an ordinary box—an intentional challenge to the preexisting idea of the art object as expressive and interpretively rich. Warhol thus plays with the tension between reality and representation, underpinning the mid-twentieth-century crisis of artistic legitimacy and the image economy of mass culture. Made of plywood boxes and screenprinted logos, and produced in a way that was more similar to the work of a large factory rather than an individual’s art studio, Warhol’s Brillo Boxes is theoretically very cheap and separated from his identity or skill as an artist. Anyone could make their own version of Brillo Boxes with very few resources or artistic skill, paralleling how factories were able to efficiently and mechanically churn out hundreds of Brillo boxes for everyday purchase. Yet, because of Warhol’s status as an artist, this fame imparts a superficially high value to his works. Brillo Boxes is still unapproachable to the audience, despite the lack of individuality or profundity that art was previously presumed to hold. Thus, Warhol thematizes the degradation of quality that was symptomatic of mass production. His works, like any other commodity, are meant to be circulated and accessed by as wide an audience as possible, showcasing the commercialization of America to a disenchanted public.

Brillo Boxes, in a blatant critique of the loss of individuality in this new age, is one of many of Warhol’s pieces that illustrates the questions of what defines art, what defines a commodity, and where—if anywhere—the line between the two can be drawn.

Some critics and scholars of Pop Art have purported the notion that Warhol’s work is characterized not by consumerist American culture, but by the way consumption disaffects the public from death and disaster. Indeed, one of Warhol’s famed series covers this theme explicitly, displaying screenprints of newspaper coverage of accidents in a way that deliberately distorts the image and lifts the photo from its emotionally charged context into a more psychologically distant presentation. Warhol’s celebrity portraits were closely tied to themes of death—like Marilyn Monroe after the actress’s suicide, or Jackie Kennedy after the assassination of her husband, the president. Even one work that appears to feature a commodity, a can of tuna fish, is undercut by the portraits of two women killed from consuming this food in the aptly titled Tunafish Disaster. But how does this alternative perspective connect to Brillo Boxes, whose product was not directly connected to any such death and disaster? When examining Brillo Boxes’s formal elements, from its iconically simplistic and bright designs to its repetitive sculptural form, this interpretation of Warhol’s work paired with a commentary on art and/as a commodity thus culminates in the death of the individual, and the disaster of a consumerist society. Brillo Boxes is composed of dozens of identical sculptures, in themselves lacking any individuality from one another or the original product. They are cheaply and impersonally made, yet attain value through the fame of Warhol’s enigmatic artistic status, illustrating the degradation of quality and superficiality of market value found within consumerism. Beyond this, their visual identicality to real Brillo boxes invokes familiarity in a broad audience, further emphasizing the death of the individual—the vast majority of Warhol’s audience, regardless of their unique identities or experiences, all recognize Brillo Boxes, all purchase Brillo boxes, and thus lose a facet of their individuality within the homogeneity of a capitalist economy.

Even in the present, the role and legitimacy of art continue to be heavily studied, discussed and debated. Some argue that art presents a challenge to consumerist culture, calling attention to the arbitrariness of ascribed monetary value and moving away from capitalist values of cheap, efficient production. Others, more cynically, may posit that art in itself is nothing but another commodity that relies on financial patronage to be sustained. Artists like Warhol, however, challenge and complicate this debate, thematizing art both as and in relation to commodities through tactics like serial replication, impersonal production, and the bold, bright graphic styles of contemporary advertising. Therefore, Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, while at face value a seemingly innocuous replication of a now-bygone product, remain integral to ongoing conversations of individualism, consumerism, and art.

Share the post: