Nymphs & Nature

Anya Adorni on feminine anthropomorphism & gender oppression

The spring without a leaf to toss, bare and bright like a virgin fierce in her chastity, scornful in her purity, was laid out on fields wide-eyed and watchful and entirely careless of what was done or thought by the beholders.

There are very few cultural signs as prevalent and, hence, as unnoticed in their impact, as the trope of “Mother Nature”. Since antiquity, from ancient Greek Gaea, Roman Terra Mater, and Basque Amalur to Algonquian Nokomis, Incan Pachamama, and Southeast Asian Phra Mae Thorani, the allusion that connects femininity and nature seems to be a nearly universal meme (as cultural anthropology defines the term). Modern cultural media perpetuates this “sentimental appropriation” (Bennett & Royle, 2016, 168) with writers such as Virginia Woolf and painters such as Frida Khalo, whose work “Roots” touches upon ecological thematology through the vessel of the feminine. The “gendering of ‘nature’” (Bennett & Royle, 2016, 167) is embedded in cultural vocabulary.

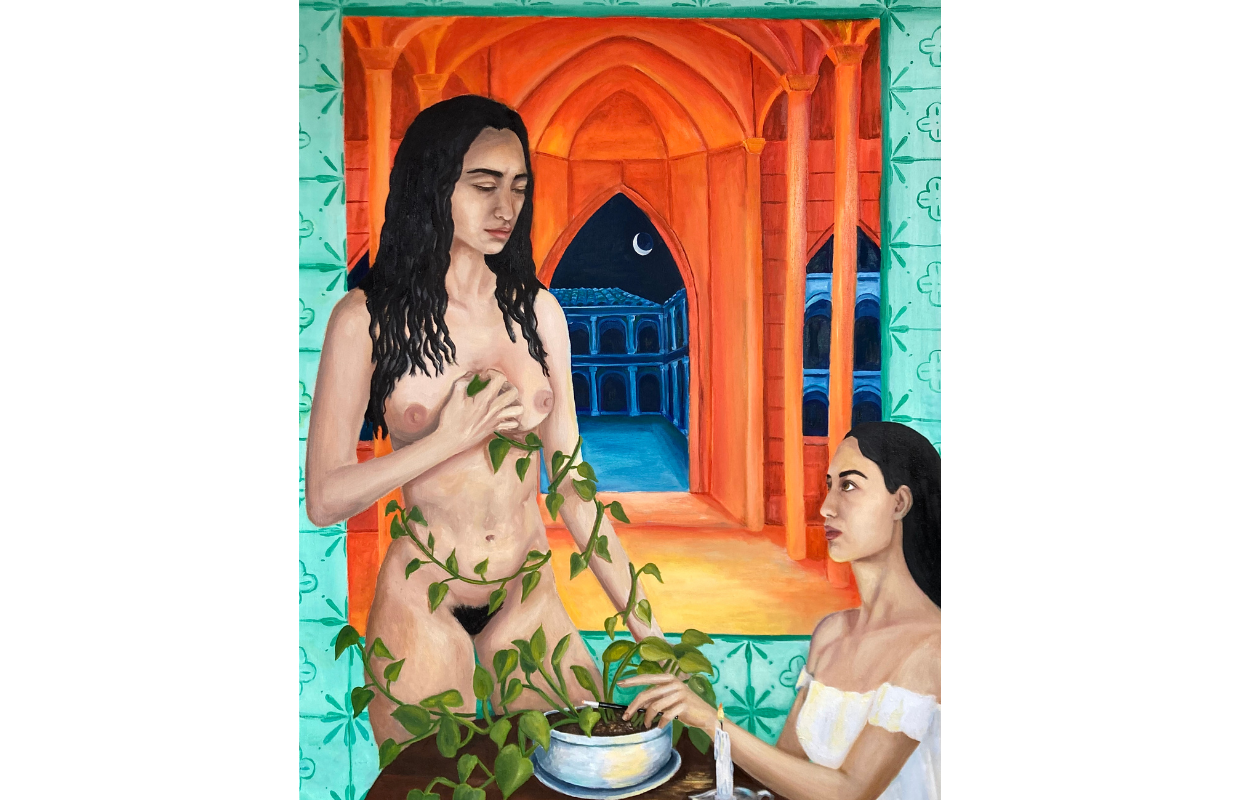

In response to the compulsive, thoughtless cultural feminization of nature and the lack of acknowledgement of the ideological devices that reproduce it, Anya Adorni challenges the “taken for granted” in her attempt to deconstruct and redefine “femininity” and “nature” through her paintings. In doing so, she engages with feminist and ecological discourse, criticizing and modifying them. Ecofeminism is the main discussion point in our conversation about the online exhibition ‘Nereids & Naiads’. In its current definition, ecofeminism is a strand of feminism that focuses on “commitment to the environment and an awareness of the associations made between women and nature” (Miles, 2018).

Woman/Nature: A two-way metaphor

Tracing the exact origin of the cultural bond between femininity and nature is a nearly impossible task. The figurative language and cultural representation of both as intertwined seem to be as old as history. According to ecofeminist discourse, especially in the context of Western culture, “nature and the feminine are linked in a gesture that denigrates both” (Bennett & Royle, 2016, 167). Feminist writers have taken issue with the default femininity of nature. Women have been systematically included in cultural similes that connect them to nature or “animality” (Ortner, 1974, 74). This argument has long been based on their reproductive role. Anya Adorni has long engaged with the impact of this reproductive role on women’s representation within society in her paintings. Through her participation in the exhibition ‘Nereids & Naiads’, from the 20th of March till the 19th of May, she brought to the forefront the association between nymphs and water as an analogy for women’s reproductive “enslavement”.

Nymphs are so closely related to bodies of water. It reminded me of how women have this constant pressure to fulfill their reproductive role. Water coincides greatly with reproduction and, through the nymphic metaphor, women are seen as objects of reproduction.

The binary opposition nature/culture seems to go hand in hand with female/male, exemplified in Edmund Burke’s aphorism: “A woman is but an animal and an animal not of the highest order” (Quoted in: Plumwood, 1993, 19). In this analogy, nature - in its separation from humanity and its identification with animality - is seen as separate and hierarchically inferior to culture. As a metaphorical extremity of this idea, women are seen as closer to nature through their reproductive role, while men are comparable to culture,controlling the military force and means of production, as well as having sole access to “large areas of the society’s knowledge and cultural attainments” (Kathleen Gough quoted in: Rich, 1980, 638). This submission of nature to culture allows for the gender power current to flow toward men. Inversely, the compulsively patriarchal societies that have been dominating Western societies for the past centuries undermine the moral value and significance of women. Hence, this simile also undermines the importance of preserving and respecting nature.

Matriarchal disentanglement

In her interview, Anya rejects compulsively patriarchal perceptions of the female body and counterproposes its matriarchal deciphering. Her interpretation of feminine materiality involves our reconnection to nature through women’s reproductive ability. For Anya, menstruation is our cruel and cathartic alarm clock ringing every month, a collective reminder of our mortality and of our participation in nature.

This is something that's happening to us that we can't control. We're dying. It's violence, but it's also kind of a wake up call. Every month you reconnect with your blood. You see your body in a different way.

Through her art, Anya criticizes the cycle of undermining that connects femininity and nature, even within feminist discourse (see Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, 1953). For her, women and the natural world are interrelated in a dynamic of power, as both are the gatekeepers of life for each other. Femininity is reminding us that materiality is one side of the “coin” of human existence, in a day and age so technocratic -it is called the “information age”, after all- that it almost entirely neglects this aspect.

We aren't thinking about our bodies. We're thinking about our heads and our eyes and what we're looking at in the world, and we're thinking about other people. The deep connection between the female body and nature can actually make us think: ‘Wait, each of us is just a body. We are a part of nature. We have no control over some things.’

E̶n̶t̶r̶a̶p̶m̶e̶n̶t̶ Empowerment

In the context of analyzing the gendered anthropomorphism of nature, we need to grasp the duality of feminine existence within societies and cultures. Within divine and nymphic myths, femininity appears as empowerment, but also entrapment, creating a ripple effect that distorts cultural ideologies surrounding the female body, womanhood, and motherhood. Spiteful of their effortless harmony with themselves and the environment around them, patriarchy envied women for their beautifully, mutely powerful way of being. In an act of aggression, it strove to strip them of their power and colonize their existence, their bodies, and their minds.

And so the legend goes, transcending from one era to the next, transforming itself from nymphic allegories to psychoanalytic case studies. Acts of aggression have been interpreted as male jealousy for female self-contentment and inclination for deep emotional life and connections (Rich, 1980, 635-636). And yet, in tracing the nature/woman as the object of oppression throughout history, examples of non-patriarchal societies arise as reminders that it is not the metaphor but its framing that constitutes the problem (or solution).

Nymphs were categorized as objects of pleasure or desire, to be pursued. They always had this empowerment derived from their allure, but it was also their prison.

The Minoan Civilization, which flourished on the island of Crete during the Bronze Age, is a beacon of (ecofeminist) hope more than three millennia after its collapse. As personifications of “fertility, nature, and rebirth” (Zorbas, 2023) in their association with the Snake Goddesses of Minoan religion, women occupied pivotal economic, cultural, spiritual, and intellectual roles. Traders, priestesses, jewelers, healers, and farmers; women were vital to the prosperity of Minoan society. Arguably even more importantly, however, they were so without compromising or modifying their femininity as a means of appeal to the male gaze. Women, as perceived within Minoan society, were peacefully imposing in their gender expression. They held power over their existence, and their power over life itself alluded to nature’s, in an analogy that not only does not undermine but actively uplifts both.

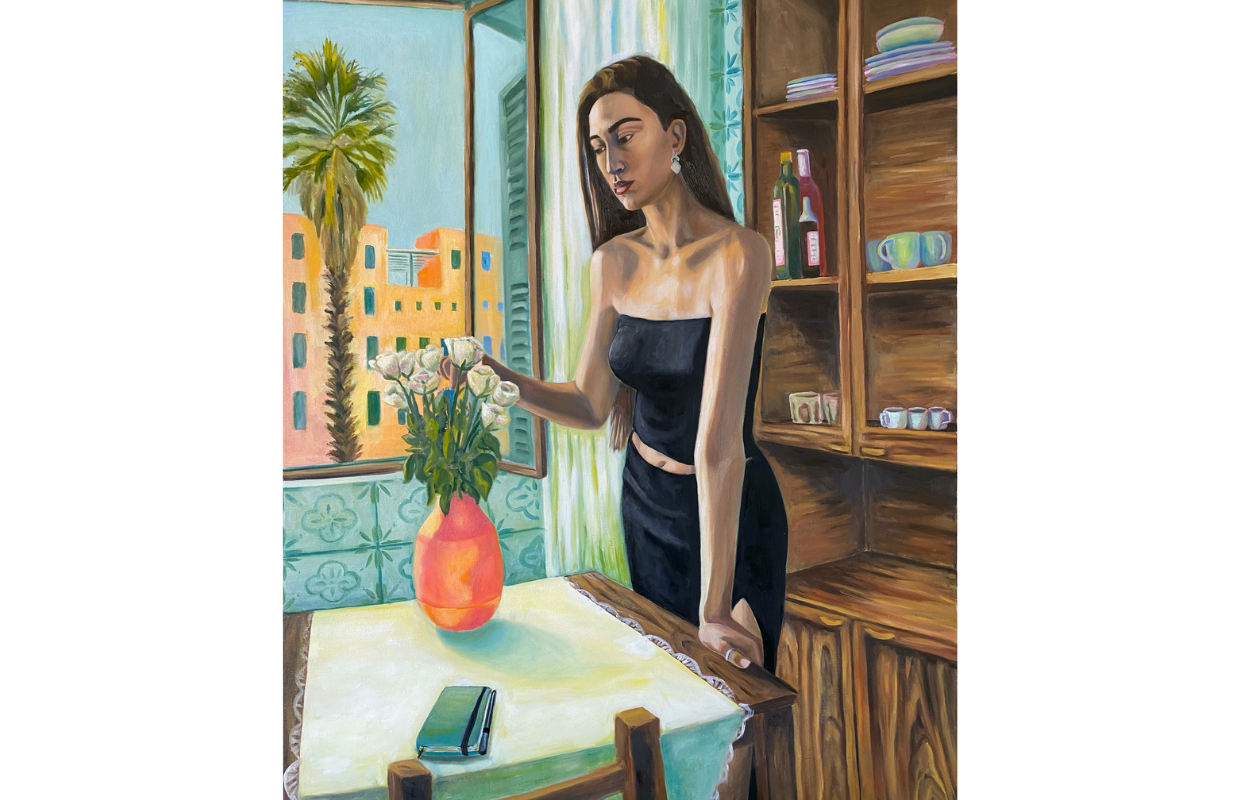

Anya inadvertently adopts the conceptual framework of the Minoan spirit, in depicting women, the female body, and its connection to a subtly alive nature. Women regain their long-lost agency in metaphorical allusions, ranging from the muted horror of natural disasters to the quiet conquering of humanity by nature. Woman/nature is reclaiming its territory after seeing it fall to the hands of patriarchal greed. Nonetheless, it is not the pushback against masculine oppression of the feminine or human aggression against the natural world that lies at the forefront of Anya’s paintings. Rather, she constructs a space reserved for feminine introspection, joyous solitude, and spiritual playfulness. A great example of her gendered humor is her painting “Those Within the Wheel”.

There's little feminist jokes thrown in, but the main point is her travel into her subconscious.

During the interview, she delved into the plot beneath the painting, laid out in an unpublished (at the time of the interview) surrealist short story explaining the intricacies of the layers of female consciousness. As the Earth literally spins out of control, she finds herself tangled in a web of uncertainty over her perception and reality. She jokes with herself, dives into the world of her creativity and obsessions, and confronts herself as a (crafts)woman, with her gendered prejudices. In the surrealist haze of the painting, both nature and woman are spiraling out of control, yet remain each contained within herself and each other.

Through Anya’s artworks, we hear a call for modern ecofeminism to acknowledge the self- and inter-containing of nature and the feminine. Their interconnectedness is not fictional, nor is it responsible for their mutual oppression. It is our cultural framework that needs to shed its colonizing, patriarchal undertones. As a first step, let us dive into the artworks of young feminist artists like Anya, get lost in the spirituality of their depictions of nature/woman, and slowly shift our collective perception of femininity and nature.

References

Bennett, A., & Royle, N. (2016). An Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory (5th ed.). Routledge.

Miles, K. (2018, October 9). Ecofeminism | Sociology, Environmentalism & Gender Equality. Britannica. Retrieved May 23, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/ecofeminism

Ortner, S. B. (1974). Is Female to Male as Nature Is to Culture? Stanford University Press, Woman, culture, and society, 68-87. https://www.uio.no/studier/emner/sv/sai/SOSANT1600/v12/Ortner_Is_female_to_male.pdf

Plumwood, V. (1993). Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. Routledge. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.proxy.uba.uva.nl/ehost/ebookviewer/ebook/ZTAwMHh3d19fNzY2NDdfX0FO0?sid=dbae864b-a4fb-4f62-bbb9-c5a7f737dc58@redis&vid=0&format=EB&rid=1

Rich, A. (1980). Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence. Women: Sex and Sexuality, 5(4), 631-660. The University of Chicago Press. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://canvas.uva.nl/courses/44782/discussion_topics/821287

Woolf, V. (1999). To the Lighthouse (Wordsworth Classics) (Wordsworth Classics) (N. Bradbury, Ed.). Wordsworth Editions.

Zorbas, A. (2023, May 23). The Power of Women in Minoan Civilization - Knossos. The Knossos Palace. Retrieved May 23, 2024, from https://knossos-palace.gr/2023/05/23/power-of-woman/

Share the post: