Echoes of "Siblings of the Soil" and the New Generation of Curators

"Siblings of the Soil", an exhibition on ecofeminism curated by Sierra Durgaram for Melkweg Expo in Amsterdam, was on view from the 8th of March to the 28th of April. In an interview with Sierra and Lina Ashour, timeless but topical insights of inclusivity in the West are uncovered while discussing the new generation of curators and artists.

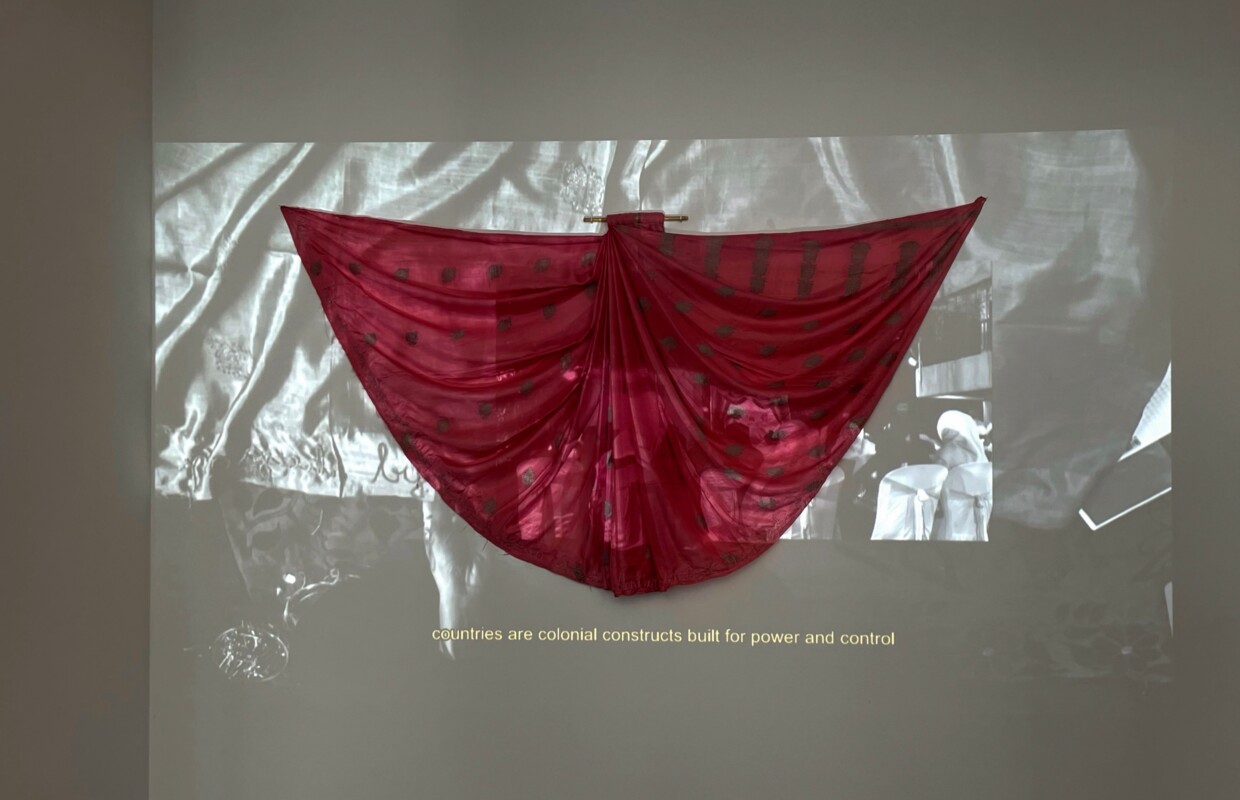

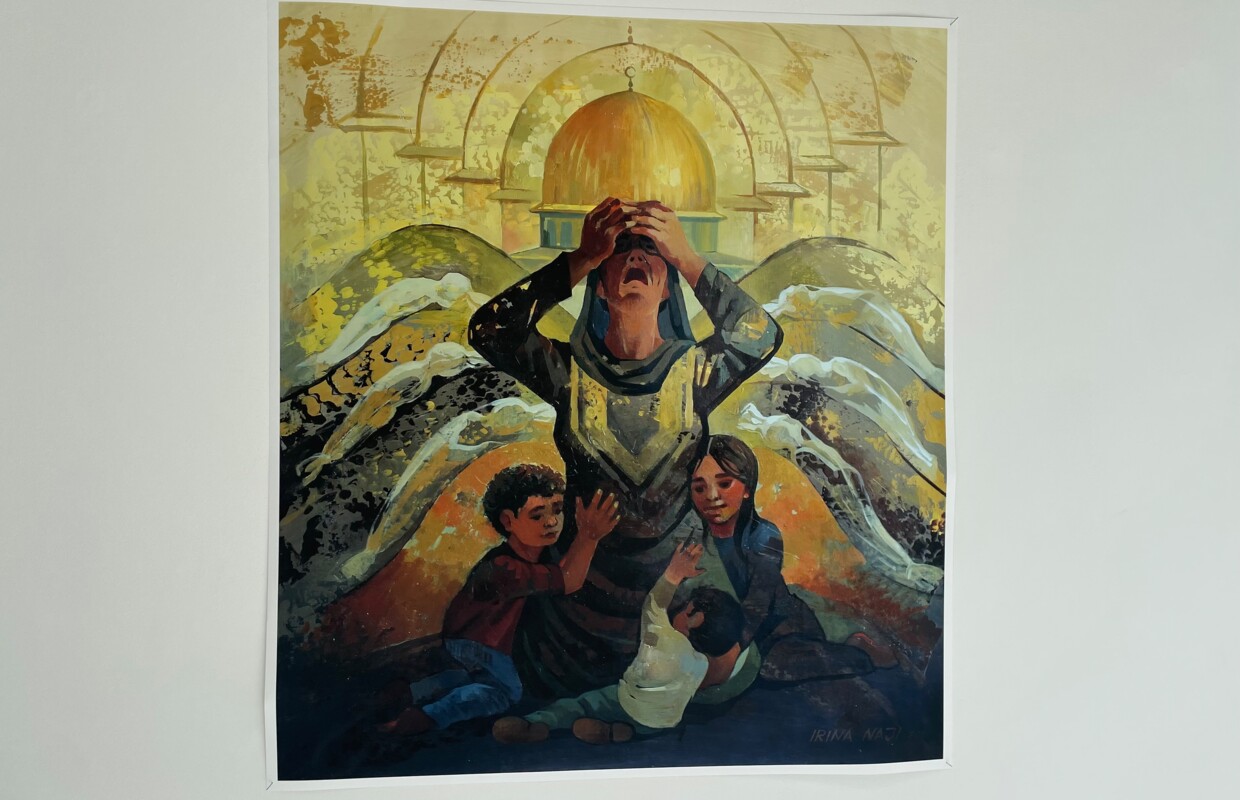

Back in April, I visited “Siblings of the Soil” at Melkweg Expo, a beautiful and powerful exhibition touching on ecofeminism in honour of Women’s day, curated by Sierra Durgaram. The words in ‘Democracy is a relic of an imagined society’, a video by Rah Naqvi, still echo in my head: “Mothers and daughters on your beige coat, a few rupees for a broken life.” The exhibition was rooted in the raw realities of women in the Global South – those whom our actions and those of our ancestors here in the West have affected the most. “Siblings of the Soil” managed to gently grab visitors by the neck and put them face to face with their often disregarded truths.

Sierra Durgaram is the founding director of Bar Bario, a safer space, creative hub, and bar in Amsterdam, which has been operating for two and a half years now. Sierra and Lina Ashour, formerly a bartender and recently the co-curator at Bario, are the two people behind curating and hosting the space’s exhibitions and events. Bar Bario focuses on prioritising artists, visitors, and employees from the queer BIPOC communities. I had the pleasure of speaking with the two during my exhibition visit.

It was the second-to-last week the exhibition was on view. Despite the unpredictable weather in Amsterdam, they were in high spirits. Sierra told me they would have a ’60s -’70s party later that night. Hence, she was dressed in a colourful chequered blazer, red tights, and was wearing bold red eye makeup, while Lina had opted for a black- and - white outfit with romantic ruffle detailing and silver accents.

Sierra told me Melkweg had invited her to curate the exhibition, suggesting an ecofeminism theme but giving her free rein with the concept. Initially amused by my request to “briefly summarise” what ecofeminism is about, she managed the task eloquently, explaining that “The earth and what humans do are always interconnected. Ecofeminism is the idea that feminism isn't only about the effect patriarchy has on women's personal lives, but also on climate change and the environment of a country. It ties these intersectional factors together.” She continued with an example of India, where a lot of clothing is made. Traditional feminism would focus on fighting for workers’ rights or breaking down sweatshops, whereas ecofeminism also takes into account the impact these practices have on the country’s environment.

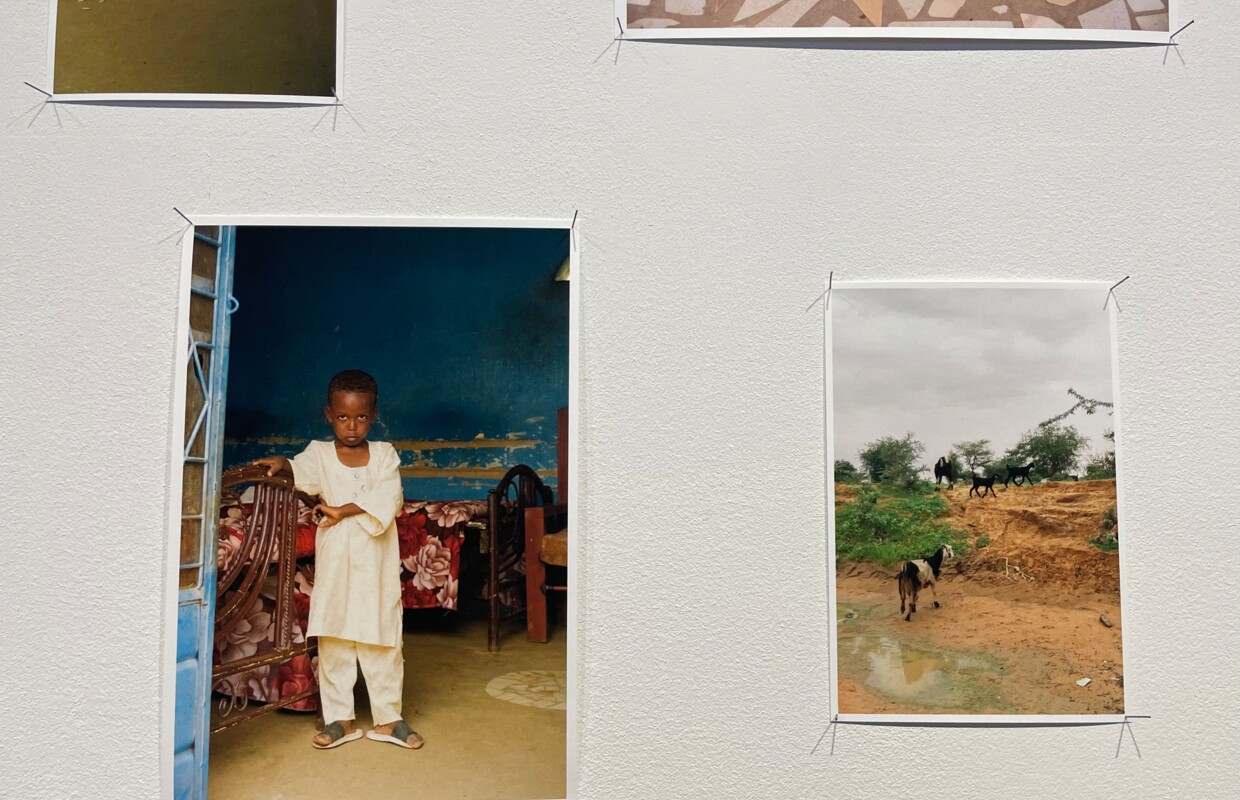

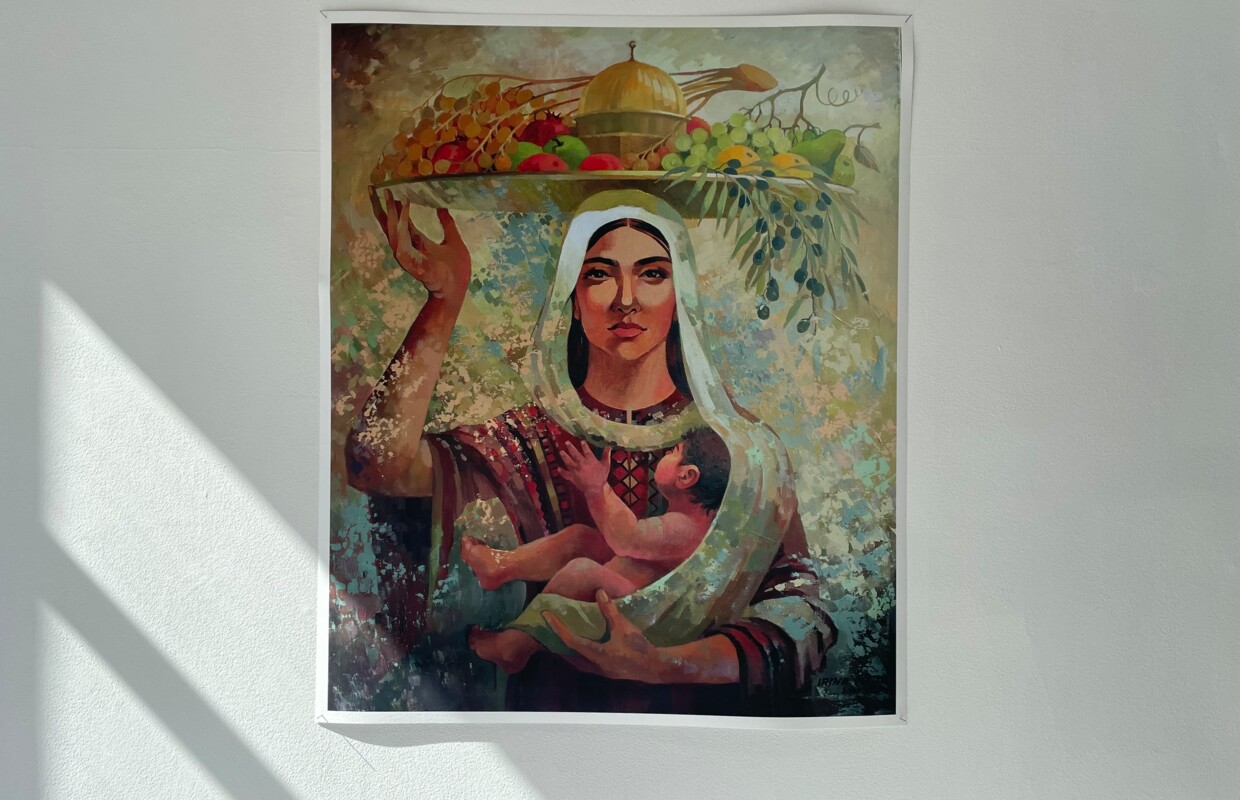

The exhibition showcased the work of six artists focusing on ecofeminism and depicting a critical perspective towards patriarchy and capitalism. The artists - Tiana Japp, Irina Naji, Maha Eljak, Dina El Zeneiny, Rah Naqvi and Nella Ngingo - presented their artworks in various forms, including paintings, photography and beadwork. Sierra recalled, “I immediately knew I wanted to choose women and femme people of colour who aren't from the Western world, because climate change, patriarchy and capitalism impact people in the global South the most. They experience the strongest negative effects, so it's only natural that their voices are heard within this theme.”

From the outside, the Netherlands, particularly Amsterdam, might seem highly progressive, but Sierra described why growing up here provided another layer of motivation for the choice of artists.

I quickly realised that what is considered feminism here, often doesn't include me as a queer woman of colour.

The same goes for the art industry. “There's always a big intersectional part of the community that falls off the radar”, Lina specified.

It felt refreshing to have a conversation bridging art and politics with people from the same generation. The topics ebbed and flowed between serious and more light-hearted ones, but the vibe stayed candid and we found ourselves laughing through a fair amount of the discussion. For example, we shared a good laugh when I asked them whether they’re both Gen Z, and ended up dubbing Lina a Zillennial.

In the words of Sierra, it’s like our generation has “this not-so-forced sense of inclusion”. They both agree that

it’s not a result of our upbringing: the desire to include as many voices as possible is something we’ve had to fight for.

Sierra explains that a visible example of this is that we’re not scared to mix politics and art, which has previously been hushed in the mainstream. Lina agreed, describing it as a kind of courageousness: “There’s this underlying understanding of ‘well, I’m here and this is how I feel, what are you going to do about it?’”

Sierra and Lina’s devotion to inclusivity and making the art world more accessible is clearly visible in their curatorial approach at Bar Bario. When asked to describe the role of a curator, Sierra interpreted that “specifically in our space, it’s definitely platforming artists and picking those who can usually only show themselves in the online sphere and inviting them in the right physical space”.

They had had an exhibition opening at Bar Bario the day before in honour of Autism Awareness Month, and Lina had invited a queer BIPOC woman on the spectrum to curate the exhibition. Lina recalled their first experience with curating when they had only been a 17-18 year old art student in high school, describing curating as “a form of communication between the artists and the vision for an exhibition or of a space that approaches Bario”. The way they see it, a curator takes on the responsibility to interpret and clearly communicate the envisioned energy for an exhibition, and to approach artists who can channel that vision.

Unlike Lina, Sierra did not attend art school, although she had considered it during her two gap years after high school. Becoming a curator was a role she took on when she opened her business. “The bar sort of fell on my path and I fully went for that. I’ve learned a lot through it. I don't know if I regret not going to school at all, at this point. Maybe sometimes!” she pondered.

Reflecting on their art education, Lina immediately reassured her it’s not a necessity. They see that the essentials for working in the art world, such as active communication, and what fuels good curatorship, come from the heart. They continued explaining that they will always promote the importance of practical experience over having a theoretical background for people that want to enrich their knowledge of the art industry.

Currently, the role of a curator could be seen as more important than ever, since art serves as a catalyst for empathy and conversations about global issues. “It’s an accessible way to get in touch with these topics.

Not everyone has the time and energy to go to panel talks, or to read books and go through all of these processes. Visual art can facilitate an immediate connection to another person with a different worldview,

She appreciates Melkweg for this reason– the space has events for everyone, which “makes that bridge of building connections smaller”. These connections can even happen unexpectedly, as the exhibitions are open through the evening, sometimes until 3 or 5 a.m on club nights. “People that aren't used to seeing only black women being portrayed, for example in photography, all of a sudden are exposed to that in a very easy way”, Sierra expressed. She jokingly noted the opening times had also resulted in some penises drawn in the guestbook, but also many sweet messages from people whose evening had been enriched by the exhibition.

Overall, both Sierra and Lina feel the Amsterdam art scene does not accurately represent the city’s diversity. Sierra argued that institutions are making small changes, either willingly or out of force, but “What I'm seeing too little is having people of colour, queer people, and marginalised people in leadership positions, instead of only having them as a prop for a certain amount of time”.

The diversity discussion feels more or less ubiquitous by now, but Lina maintained that it still doesn’t go deep enough to actually be fruitful. They made the point that “The depth, the level of accountability and the responsibility that goes with it is just not the same with everyone”.

To further illustrate this, Sierra added that “the big arts institutions are trying, but they're only giving artists exposure instead of inviting them to the decision making table. Also, museums can now add tags next to artworks saying ‘we actually stole this piece’, but instead of giving them back, they're just mentioning it. That's the general vibe I'm getting: awareness, but not a lot of action.”

Ultimately, something that we kept coming back to was that this leads to many institutions simply lacking the perspective to make decisions of the representation of these communities. While it’s good to have their works out there, Lina thinks

the affected people in the community will feel and notice whether a portrayal is genuine and has a certain depth and honesty to it.

When it comes to choosing artists to exhibit, they added that institutions should strive for a more balanced approach: to be genuinely interested in showcasing the talent of artists, who coincidentally also have a marginalised identity, instead of plain tokenism.

Seeing other spaces prioritise the ‘Bario approach’ is what brings joy and gets them excited, according to Lina. “We like to see spaces share the same philosophy. For example, The Social Hub, where Sierra is also invited for an exhibition.” They explained that in Amsterdam, it is still mostly visible in smaller galleries, using Expo in Noord as another example.

Initially, there was a long silence after I asked about other Amsterdam art spaces or institutions they thought were making good progress in inclusivity and accessibility efforts. However, after Lina had mentioned Expo and The Social Hub, Sierra also wanted to shout out OSCAM in de Bijlmer, and MOTORMOND. “Those are small gallery spaces, but they’re definitely for us, by us. That's a notion that we represent as well”, she pointed out.

That also brought us to discuss the commercial side of the art world. The artworks that were a part of Siblings of the Soil were not for sale, but QR codes on the wall allowed visitors to directly inquire the artists about their pieces. Her and Lina find the art industry’s secrecy surrounding pricing kind of funny. “Transparency is always good. I get the idea of wanting to keep the commercialised side out of your galleries, but that's what gallery spaces are for, right? You can't eat from exposure, so you're gonna have to sell some works at some point!”, Sierra chuckled.

The artists need to eat, but entering the market, exhibiting and making sales for the first time can be easier said than done. With the Bario approach to curatorship, Sierra and Lina have given a lot of artists the opportunity to present their work for the first time in real life. As a result, they have seen emerging artists grow confidence to reach out for opportunities themselves.

It has also forced the artists to learn how to network, present themselves and their work face to face with people, skills that the two find crucial to master in the industry. Sierra acknowledged that “it’s the shittiest part of being an artist – it’s not only about the art, it’s also about you”. She added that it shouldn’t be necessary to build a persona, but just being a person and knowing how to speak about your work “can make it easier for others to understand it and to want to exhibit it or buy it.”

The two strongly believe that persistently putting yourself out there pays off. Talking about how most people apply to exhibit or host an event at Bario through Instagram or an open call form on their website, Lina wanted to reassure that

Even if it feels like you're throwing yourself out there and nothing is coming back, we still notice it.

"If you're reaching out and we're not responding, you’ll still be in our memory." They explained that actually, in a month or two they might end up having the right space for that person.

Sierra told me most of the time finding artists, for example surrounding a specific theme, happens through Instagram but also via word-of-mouth inside the community. Commenting on the role of digital platforms in the art industry, she stated: “I do see a lot of people getting a platform through Instagram and TikTok and stuff like that. But, it's kind of sad that you have to stimulate people so much and go beyond what your art is intended for, because you have to make a Reel and this and that.”

We fondly reminisced on curating a personal Tumblr page, comparing it to an exhibition space. Lina would describe its close equivalent, curating a business or personal Instagram page’s feed, to visiting a museum: “Once you have that down as an artist, sometimes when I'm scrolling through their feed I feel like I'm in a museum. It can feel very high engagement, but you just have to create that lens.” A feed could help reveal some of the context and humanity behind an artists’ work online, but both of them would still like to emphasise the importance of having the possibility to eventually connect face to face.

Social media has provided a constant opportunity not only to explore artists' works, but also to learn about their beliefs and political stances, which, if they clash with the viewer's views and morals, can turn them away for good. Of course, some choose to separate the art from the artist, but Sierra doesn’t think that it’s feasible.

“An artist represents how they feel, what their views are and who they are through their artworks.” She used the case of J. K. Rowling being a Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist (TERF) as an example, and recited how she had seen a Twitter thread pointing out excerpts of the Harry Potter books that demonstrated the authors’ views. Hence, even if indirectly, supporting a questionable artist can also support their harmful causes. She acknowledges that it’s a hard conversation, but personally doesn’t feel the need to be in cahoots about it. To her, being attached to someone’s art despite clashing morals seems unnecessary, since there are a myriad talented artists out there with perspectives that match hers.

Lina agreed that moving onto something different can be a powerful thing to do. On the other hand, they can see why people keep supporting contested artists. It’s one thing to relate to someone’s political views or ideology, but “The way you relate on an emotional level with other themes that come up in their art is another”. They exemplify the difficulty of the matter by mentioning the current debate about whether it’s justified to keep listening to artists in the music industry who are not speaking up about Palestine. They let out a deep sigh before admitting to “struggle with that a lot. Sometimes I'll think, ‘damn, I do want to engage with this art form right now, even though the artist is tainted by who they are.”

After our conversation, we hung out in the exhibition space for some time and did our things: I took photographs of the art, and Sierra and Lina made TikToks to promote it on Bar Bario’s Instagram. I asked to take a photo of them, for which they made sure to wear their keffiyehs, and we said our goodbyes, all excited for what’s to come.

I could still clearly see the gentle beams of afternoon light that poured through the enormous Dutch windows of the exhibition space, on a day otherwise filled with violent rain showers. In the middle of the city, mother nature was literally doing what the exhibition aimed to do: illuminating the perspectives of those too often ignored in the West – Women of Colour – through art. And after the sun had casted light on the artworks, it felt impossible to look away. They enlightened the visitors in turn. I imagine I’ll be reminded of “Siblings of the Soil” whenever I think about the subtle but strong power art has – via platforming inclusive, genuine representations – to unite people, and to set them free.

Share the post: