The City and the Arts

Can artist communities withstand the rising cost of living?

Most conversations on the rampant increase of real estate prices begin and end with New York City. In 2020 and 2021, as COVID wreaked havoc and weakened the real estate market, both New Yorkers and foreign investors were lulled into a false sense of security: eventually, they thought, New York’s housing bubble would pop. In those two years, the rate of families moving out of the city tripled and property prices fell sharply – the general understanding was that most people would leave Manhattan as remote working made offices obsolete. One pandemic later, people are back and, as it turns out, so are pre-pandemic prices. As of 2023, New York, tied with Singapore, is still the most expensive city in the world, and the value of its real estate has surpassed 2019 numbers. This is wholly unsurprising: the city remains infinitely attractive, packed with job opportunities, entertainment, food and art.

The presence of the art world and the art market in Manhattan is conspicuous and imposing. Some of the most important museums in the world line the main avenues of the Upper East Side and museum-sized galleries dot the streets of Chelsea and TriBeCa, with new openings every day.

What is becoming increasingly less evident, however, is the presence of a community of artists, a network behind that market.

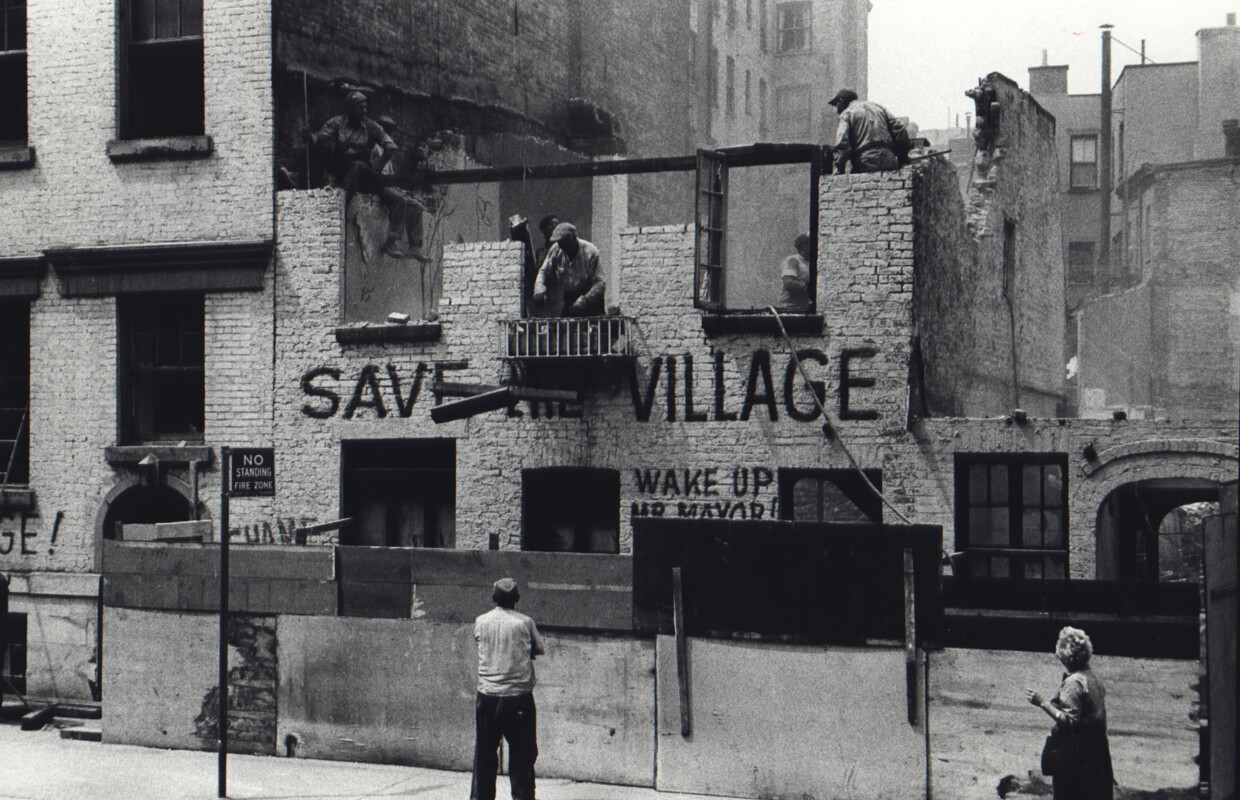

Every era of modern New York has boasted its own neighbourhood of artists, acting almost as a physical manifestation of the cultural milieu of the city. These neighbourhoods have always been vital spaces for New York's social fabric: aspiring artists from all over the world could find a haven in this or that neighbourhood, moulding what were the least desirable areas of the city into dynamic cultural enclaves.

The Village was the epicentre of the beat community in the 50s and early ‘60s, but when the area became celebrated and its property attractive, immigrant neighbourhoods in the Lower East Side (which were rechristened “East Village”) and the large industrial lofts of SoHo and TriBeCa, became the new destination for visual artists in the ‘70s and ‘80s. By the late ‘90s, increased value prompted galleries to relocate from SoHo to Chelsea, setting up shop in large industrial complexes that originally housed shipping containers. When Chelsea became “it” and prices were too high for young up-and-coming artists, they moved across the East River to Brooklyn neighbourhoods such as Williamsburg.

Each of these neighbourhoods has its own, rich history, but the trajectory of their transformation is similar: young, creative people move into an undeveloped neighbourhood, improve its aesthetic and cultural appeal and end up pricing themselves out of it.

Names such as NoHo, SoHo, TriBeCa, Nolita are the result of these rebranding experiments that turned neighbourhoods around, gentrifying them into the most expensive areas in New York and the entire US.

Of course, it’s natural for a city to improve its standards (and the value of its land), but when these changes are especially rapid, localised and disruptive, they are telltale signs of gentrification. This process is exactly what is happening now in so many New York neighbourhoods. If one looks at online lists showing the “places to be” for young artists, they seem to take us further and further out: Red Hook, Navy Yard and Sunset Park, in the outer parts of Brooklyn, Inwood and Washington Heights, in the upper tip of Manhattan, Mott Haven, in the Bronx, Jersey City and Newark, across the Hudson and outside the state of New York. History suggests that in ten years these neighbourhoods will be as expensive as the ones creatives are fleeing now.

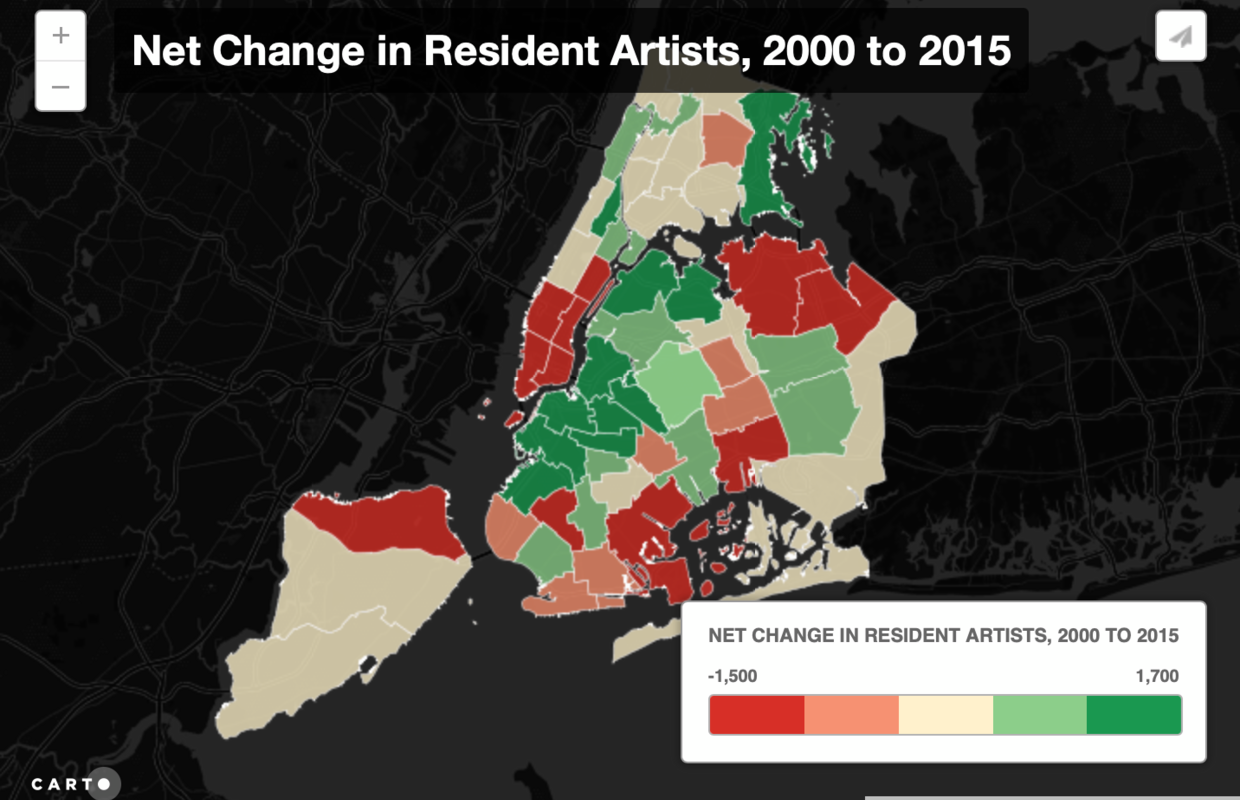

The CUF (Center for an Urban Future), a body organising policies for a fairer and more equitable city of New York, have published maps showing the net migration of artists in and out of the city’s boroughs and neighbourhoods. As expected, from the 2010s to the 2020s artists have moved in droves outside of Manhattan – a move that is not unique to their demographic, but that in many ways seems to be spearheaded by it.

So what is the bottom line? Is the escape of artists to more and more marginal areas of the city inevitable? Is it a bad thing at all? If we look at the cultural capital of the city at large, it might just be. When artists live in close proximity to the urban centre – as they did in the golden age of Greenwich Village or when Lower Manhattan’s heavy industry was replaced with exciting visual art – a dialogue between an established artistic culture and fresh, countercultural waves of new ideas can’t be avoided.

When the establishment and the innovators collide, both sides of the conversation must be heard. It’s not only a question of marginalisation, either: as artists move out, their communities are dispersed and diluted.

From a small number of strong communities to a large number of weaker ones, we are redefining the meaning of “creative neighbourhood” – a feeling of unity and cohesion is disappearing along with the abilities of artists to share their experiences with their neighbours and colleagues.

Though it’s true we live in an age where cultural interactions might happen on platforms other than in-person conversations and that social media has given artists infinite opportunities to share, exchange and amplify their experience, there is still power in numbers and a community’s activity within a city. If young people with something new to say are pushed outside then that conversation can become redundant, stagnant. If we lose the value that vibrant creative communities bring to New York City (and the many other artistic capitals) we run the risk of stifling their voice, and this will keep happening if the correlation between the unaffordability of the real estate and cultural relevance remains so strong.

Since 2020, many young artists are moving out of the city entirely, relocating to areas such as the Catskill Mountains and the Hudson River Valley. Once again, this proves that affordability should not be the only metric by which we look at this phenomenon. The ability to form a tight-knit community with like-minded creatives and the resulting cultural exchanges, which make these rural towns so attractive, are just as fundamental. If the city stops providing those kinds of opportunities, its cultural power, both in the US and the world, may not last forever.

Share the post: